As Kamloops celebrated Canada Day last week, some may be surprised to learn the occasion’s history is actually relatively short — and more complicated than the annual popular festivities may suggest.

The holiday wasn’t even named Canada Day until 1982, after former prime minister Pierre Trudeau replaced the 1867 British North America Act with the country’s first domestic constitution, including the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

It was a pivotal moment for the country’s evolving identity. In fact, for more than a century, Kamloops and much of the country celebrated the previous national holiday — Dominion Day.

For much of the 20th century’s first half, the holiday was more a celebration of Canada’s place within the larger British Empire, not a celebration of the independent country we know today.

In Kamloops this was marked by a grand parade until the 1960s, when the summer parade was replaced by one for Indian Days, Kami-Overlander Days, Spoolmak Days and others.

Colonial historical revisionism on display

These celebrations included historical revisionism, often exaggerated and mythologized the role of white, and most especially British settlers, while erasing important contributions of both Indigenous Peoples and Chinese-Canadians.

For instance, in 1912 the city held a fake centenary event, in which celebrants claimed Kamloops was “founded” when the fur traders opened the first trading post near the Secwepemc village at Tk’emlups.

And a quarter-century later, the Hudson’s Bay Company sponsored a 125th “birthday” parade for Kamloops as part of the 1937 Dominion Day festivities, despite the city being only 44 years old, since it was officially incorporated in 1893.

The narrative of rugged white pioneers taming an “empty” wilderness — a concept dating back nearly a millennium — was on full display, despite the truth that fur traders mostly co-opted long-established Indigenous Nations’ trade networks and trails. Although July 1 organizers sometimes did invite Tk’emlups te Secwepemc to participate in local events, the nation refused to play along with its own erasure.

Each time, leaders delivered the same message: “We were here first.”

Racism-fuelled resistance to being labeled ‘Canadian’

So how did we get from glorifying the British Empire to celebrating Canada on July 1?

What stood in the way of developing a unique Canadian identity and what 20th-century events forced that to change?

Let’s examine through a Kamloops-centric lens.

By the 1920s, a sentiment was growing among those born in Canada, especially in British Columbia, that they should be able to identify their nationality as “Canadian” on the census and other official documents.

The standard of the time was to list their father’s nation of origin, unless he was also Canadian-born, in which case one’s most recent foreign-born paternal ancestor’s nation of birth was listed.

For many this ancestor was many generations removed, and the system also ignored the influence of maternal relatives on personal identity.

What did it matter if their paternal great-great-great-great grandfather was born in Wales, if they also had English, Scottish, Norwegian, Cree and French ancestors?

How could you call yourself a Scotsman if no ancestor of yours had set foot in Scotland for nearly 200 years?

There was also significant resistance to the development of an independent Canadian national identity.

In a 1923 letter to the Kamloops Standard-Sentinel, Clyde Harvey Dunbar expressed his opposition to the Native Sons of Canada — a fraternal society similar to the Knights of Columbus, but for white Canadian-born men. He argued that the “reason for the adherence to nationalities of origin… [was] so obvious” that he felt it barely needed explaining.

“If we are to declare ourselves Canadians only we include Canadian-born Chinese, Japanese, Italians, Slavs and all the other races on the same footing… Most certainly that is undesirable,” he wrote. “Surely the day has not come to Canadians when they are so solicitous to be called Canadians rather than English or Scotch that they will eliminate the safe-guard against becoming something essentially different!”

While Dunbar noted in his letter that he was Canadian-born, he neglected to mention his own nationality was actually Irish under this system, the lowest on the British Isles’ internal racial hierarchy.

Perhaps, some might say, his reaction was based in fear of losing any privileges his family had gained by leaving Ireland and moving to Canada.

Either way, his concerns that the Native Sons of Canada might lead to the acceptance of non-whites as equal Canadians was unfounded.

The organization and its women’s auxiliary, the Canadian Daughters League, shared his racist views until its dissolution in 2015.

‘Humiliation Day’ for second-class Canadians

From 1923 onward, Dominion Day had another name among Chinese-Canadians: Humiliation Day.

The day was so called after the July 1, 1923 passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned Chinese immigration to Canada — with very few exceptions — until its repeal in 1947.

Chinese-Canadians boycotted Dominion Day festivities for the duration of the ban, and many declined to participate long after it was repealed.

People of Chinese ancestry were not the only Asians discriminated against by Canadian immigration policy.

Although not affected by the anti-Chinese Head Tax or Chinese Exclusion legislation, both Japanese and South Asian people also found themselves targeted by racist policies — for example the restriction against immigrants who didn’t arrive via a continuous journey from their home country, despite no such voyages being available.

Asian-Canadians were also barred from voting and serving on juries, as well as having certain careers such as doctors, lawyers or pharmacists.

Besides ethno-nationalism and xenophobia — fear of the “other” — an economic argument fuelled anti-Asian sentiment in British Columbia and Canada as a whole.

Many white people were angry about immigration, claiming their jobs were at stake and their wages were being undercut by Asian immigrants who accepted the lower wages employers offered them.

The anger, however, was rarely directed at the employers who got away with paying non-white workers less.

Tensions between British and Asian-Canadians would come to a head during the Second World War.

That devastating conflict was a catalyst for change.

The first shift in public opinion came when the Japanese Imperial army invaded China in 1931, creating the puppet state of Manchuria.

Reports of the brutality of the invaders against the Chinese civilians garnered outpourings of sympathy and prompted Canadian citizens to raise money through relief drives.

Feelings of sympathy and goodwill continued to grow as the Sino-Japanese conflict intensified and war broke out in Europe.

When the 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor pulled the allies into the Pacific theatre, the Chinese found themselves as allies to the British Empire.

Chinese-Canadians, initially rejected from military service, were recruited to serve overseas.

But Japanese-Canadian civilians were in the opposite position.

Despite playing no role in the Empire of Japan’s invasion, they were officially labelled “enemy aliens” — and within weeks, all people of Japanese ancestry within 160 kilometres of the Pacific coast had their businesses and property seized and were rounded up to be sent into internment or labour camps.

Other anti-Japanese exclusion zones were set up around areas deemed to be of military importance.

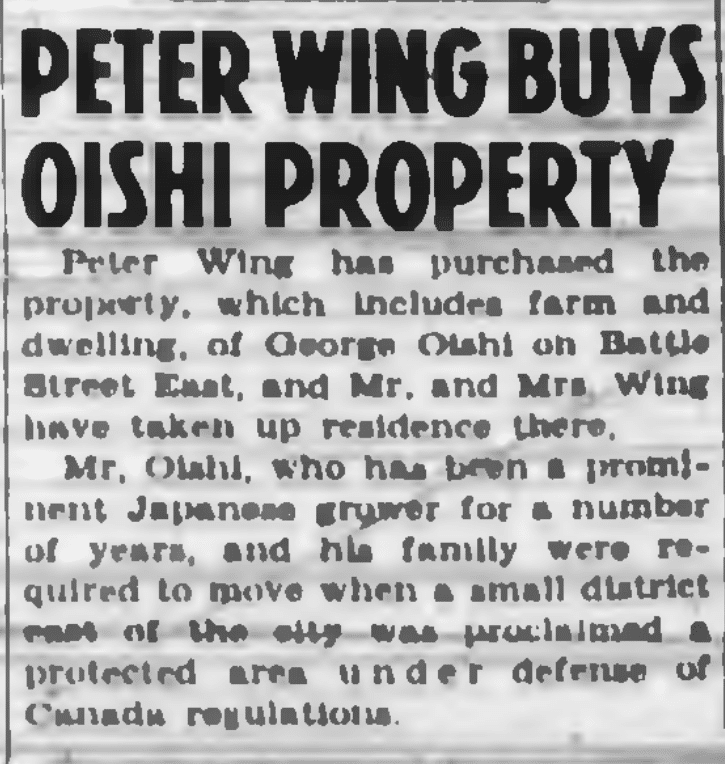

Of the seven Japanese families already living in the Kamloops district at the time, only one — George Oishi’s family — was affected by the new policies.

Even though their property was far from the coast, they faced seizure and forced sale because of a munitions cache planned beside their property.

That was until Chinese-Canadian Peter Wing bought their farm — now the Orchard’s Walk subdivision in Valleyview — at fair market value, allowing the Oishis to buy a new property to continue farming nearby.

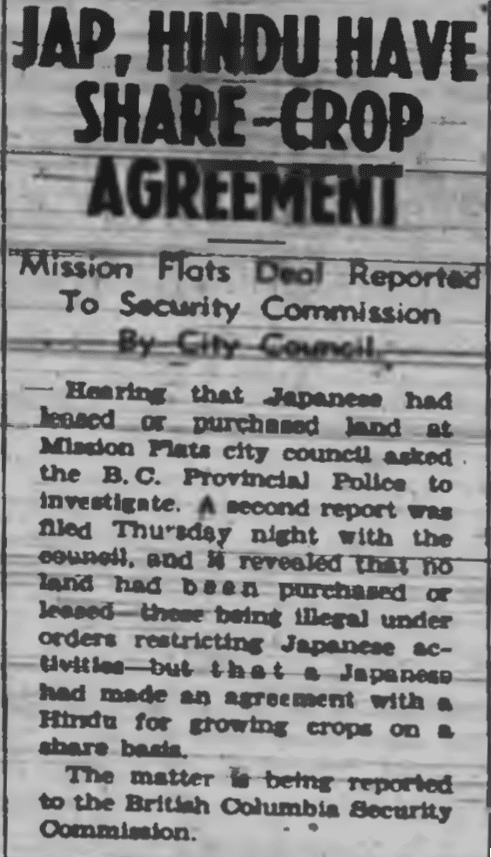

This was not the only example of Asian-Canadian solidarity during the war years.

Japanese families could avoid the harsh conditions of the camps by having a special permit issued if they could find an employer willing to provide jobs and lodging. Many local Indo-Canadian farmers stepped up to do just that.

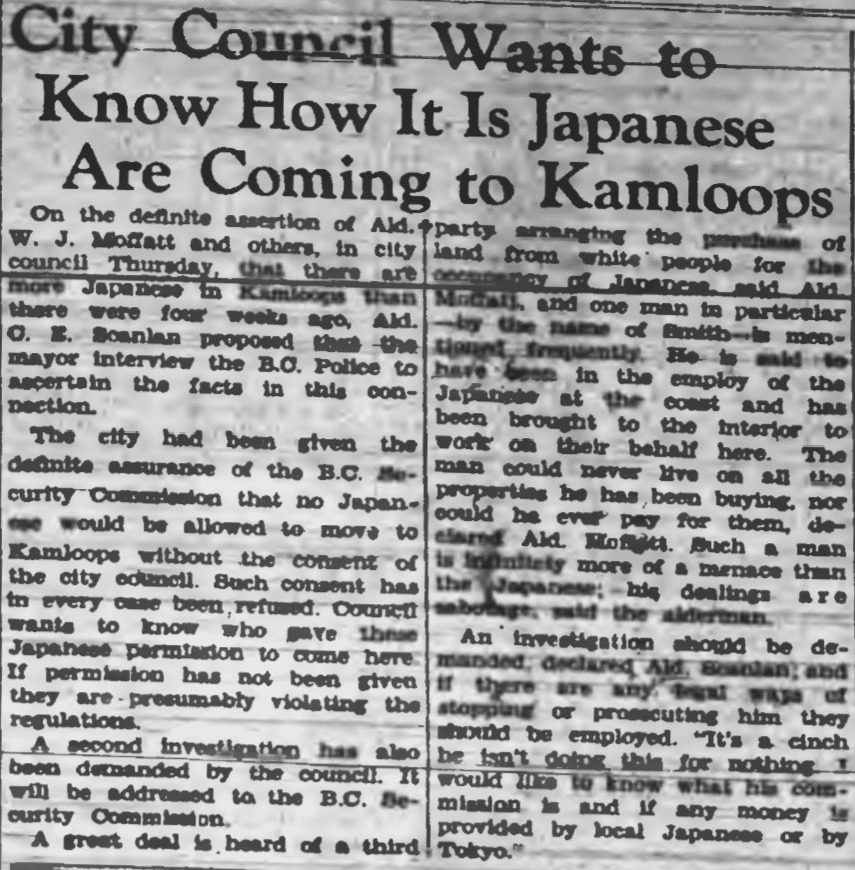

Municipal councils outside the restricted coastal zone were given the option to deny migration of Japanese-Canadians within their boundaries, which the Kamloops council did immediately.

This action was fervently supported by the Kamloops Board of Trade and local newspapers.

Unfortunately for the council’s hope to exclude migrants on racial grounds, the city limits of Kamloops at the time were small, effectively encompassing only today’s downtown area.

It had no power to stop Japanese Canadians with special permits from migrating to what is now the North Shore, Valleyview, Aberdeen or Mission Flats, and those individuals were free to patronize businesses in the city during daytime hours.

But Kamloopsians of many ethnic backgrounds refused to take part in the city council’s anti-Japanese hysteria. For example, Kamloops School Trustees refused to block the enrolment of Japanese children.

About 200 Japanese families had soon migrated to the Kamloops area, and were reportedly well-liked by their neighbours.

The matriarch of one such family who lived and worked on Sher Singh’s Brocklehurst farm during the war recalled in a 1984 interview that “she never had any problems with the neighbours, or with discrimination.”

She attributed the friendly relations to the fact that “Germans, Ukrainians and East Indians …perhaps understood the effects of discrimination better than anyone.”

By the end of 1943, city council admitted that “the behaviour of the [Japanese-Canadians] had been exemplary,” yet still “saw no reason” to reverse its discriminatory stance.

The atrocities of the Second World War had been publicized through photographs, film and audio in a level of detail never before seen. These horrors began to temper deeply entrenched racism held by many.

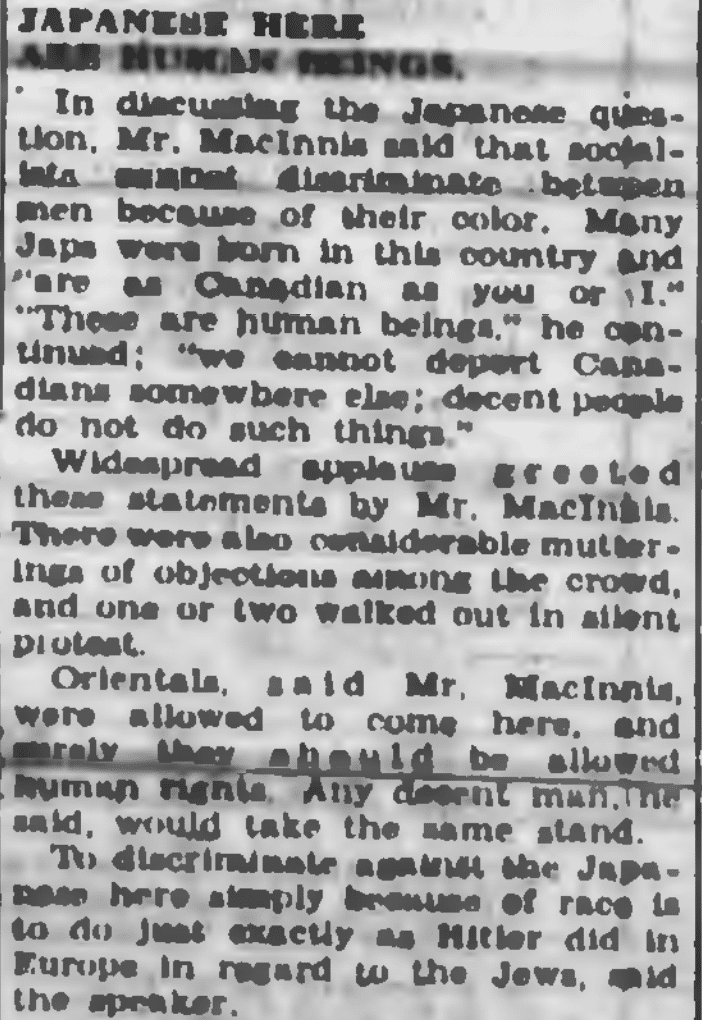

In British Columbia especially, the uncomfortable parallels between the extermination campaigns abroad — both by the Nazis against the Jews and others, and by Imperial Japan against the Chinese — and the internment and displacement of Japanese-Canadians hit very close to home.

An estimated three-quarters of people displaced and interned here were actually Canadian citizens — and two-thirds were born on Canadian soil. Canadians of non-British heritage began to wonder if the same could happen to them.

Multiculturalism takes root in post-war Kamloops

Hate did not evaporate overnight, and racism in Canada was not solved in 1945.

But the war and its aftermath marked a turning point in public opinion on human rights and the rights of Canadian citizens.

The overt and often officially endorsed torrent of anti-Asian sentiment diminished amidst growing calls for equal rights for all Canadians.

While the 1920 Dominion Election Act granted Asian-Canadians a vote, it also let provinces block that right — a policy British Columbia used against citizens of Chinese, Japanese and South Asian ancestry.

Canadian veterans of Japanese, Chinese and South Asian descent were finally granted the right to vote in provincial elections in 1945 with an amendment to the Provincial Elections Act.

In 1947, the Chinese Exclusion Act was rescinded; Chinese and South Asian British Columbians were given full voting rights, and bans ended on their participation in juries and certain careers.

Two years later, the same rights were extended to Japanese-Canadians in B.C., and war-time restrictions on their movements were eradicated. That year also saw B.C. grant Indigenous people the right to vote in provincial elections, although they would not have the right to vote in federal elections until 1960.

By the 1950s, Chinese-Canadians and Japanese-Canadians were participating in Dominion Day parades.

In 1966, the City of Kamloops took a major step forward when voters elected Peter Wing — who’d purchased the Oishi orchard in 1943 — as mayor, the first person of Chinese descent to hold the title on the entire continent. Interestingly, he was also Kamloops’ first locally born mayor.

A new Canadian identity was being forged, based on multiculturalism.

That is not to say there was not still more work to do, as the Tk’emlups te Secwepemc reminded Kamloops during the 1953 Dominion Day parade. But that story is a very interesting story for next time.

So do we. That’s why we spend more time, more money and place more care into reporting each story. Your financial contributions, big and small, make these stories possible. Will you become a monthly supporter today?

If you've read this far, you value in-depth community news