For the past 23 years, Dieter Dudy has spent Saturday at the Kamloops Farmers’ Market. What began as a one-table operation for the Thistle Farm founder and owner is now more than three tables long — “and it’s still not enough,” the farmer says.

On a blustery September Saturday, a colleague works the scale as Dudy labels his produce. There’s squash of odd shapes and sizes: acorn, delicata, butternut, spaghetti, sweet dumpling and gem. There’s cabbage, kale, tomatoes and beans. And many peppers: Sweet bell and green; poblano and serrano.

“We like to introduce people to new things,” Dudy tells The Wren.

Having produced food in Kamloops’ Noble Creek area since 1997, “you get to know what people want,” he says. He jokes that his corner stall at the Third Avenue entrance has become “the Costco of produce at the market.”

It’s been a productive year for Thistle Farm, something about the combination of heat and moisture over the summer, Dudy says.

But now the farm’s irrigation source is at risk, and Dudy, a former city councillor who served from 2014 to 2022 before being named runner-up in the 2022 mayoral election, isn’t sure what next year will bring.

On Sept. 5, after years of discussion and directives, Kamloops city council voted to decommission the Noble Creek Irrigation System (NCIS), which supplies water to 41 users in the Noble Creek area, just north of the Westsyde.

Leaving the half-a-century-old irrigation system in place was too risky, city staff had previously told council, and the city had to make a call after debating the issue in closed meetings for months.

On Sept. 30, at the end of the irrigation season, the system was shut off. And while the city is exploring options for a temporary irrigation supply for the 2024 season, no one — including city staff — knows if irrigation will continue.

Noble Creek Irrigation System through the Years

The city has largely neglected the Noble Creek Irrigation System since it took ownership in 1973 during amalgamation, along with other B.C. Fruitlands assets. Over the years, it has offered many reasons for decommissioning the NCIS: bank erosion, costs of running the system and provincial regulations.

Bank stability issues began in the 1990s, says Cat Lapointe, whose partner, Justin Fellenz, owns 39 acres just upstream of the intake.

In 2008, the city budgeted $740,000 to address the issues, but the funds were reallocated without the work being completed.

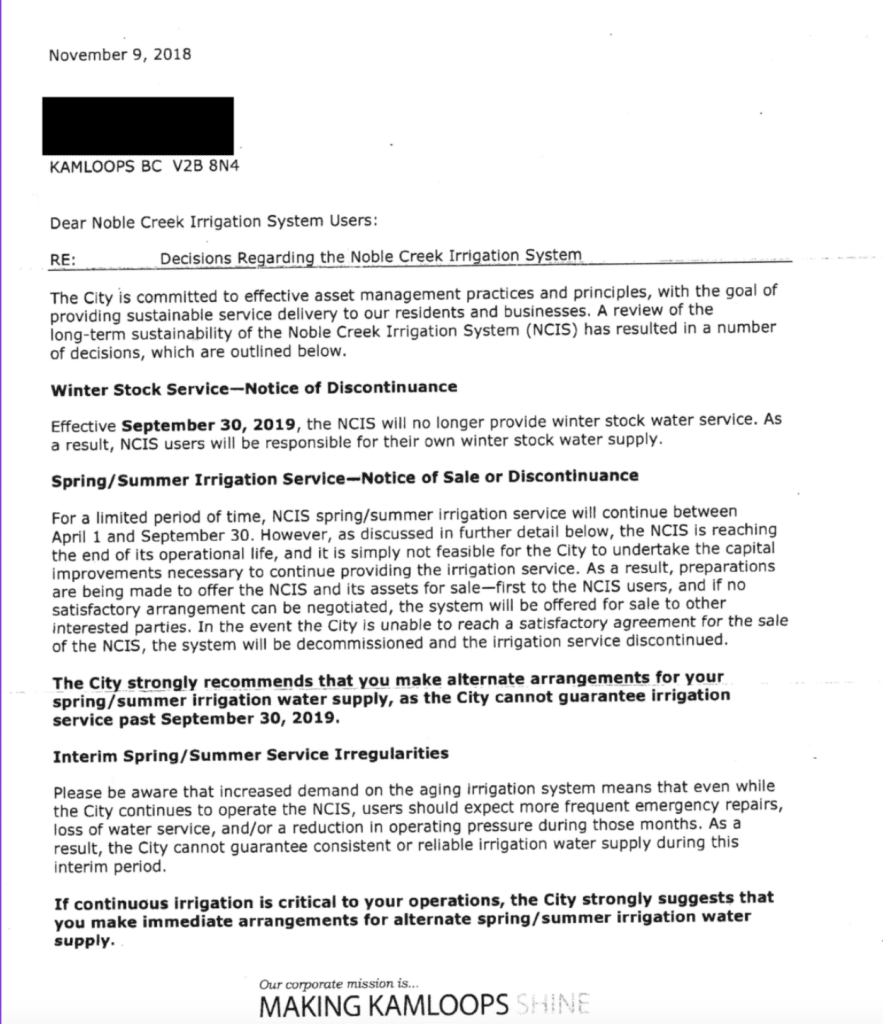

Things were quiet for a few years. Then, in November 2018, the city sent a letter to NCIS users saying the system would be shut off for good at the end of the irrigation season, in about 10 months, unless users bought it from the city.

Users fought to keep the system running, and a decision on the NCIS was reserved for another two years.

In 2020, the city told users it would rebuild the NCIS if they footed most of the bill — 80 per cent of $14 million, an estimate provided by Kamloops engineering firm Urban Systems.

The cost would have put farms out of business. For Fellenz, he says it would have meant a $400,000 lien on his property. Users appeared as a delegation and convinced council to cancel the project.

What’s wrong with the Noble Creek Irrigation System?

The erosion at the site is undeniable and has continued at an accelerated pace, fuelled by intensified cycles of drought and floods as a result of climate change, with more than 20 metres of bank lost in the last year and a half.

The bank is now much closer to the Noble Creek Irrigation System’s on-shore infrastructure: a pumphouse and the settling ponds. The city is worried about that infrastructure eventually falling into the river and its liability.

“We’re in a really hard place,” Lapointe says. “Now we’re not just going up against bureaucracy, we’re going up against Mother Nature.”

The NCIS uses a 350-horsepower pump to pull water from the North Thompson River. The water contains a lot of sediment — known in the utilities business as high turbidity — so it passes slowly through a reservoir, allowing a lot of that sediment to sink. From there, the water is pumped through pipes to users.

By 2010, treated water infrastructure reached Noble Creek — before this, the NCIS also supplied drinking water. The NCIS water is accessed at a cheaper rate than the city’s treated water.

The irrigation system is running at a deficit in part because the infrastructure is unmetered. Rates for the 41 users are based on the size of the irrigable property and range from $63 to $11,516 annually.

City of Kamloops utilities manager Greg Wightman says they tried to meter it once in the early 2000s, but because the meters were designed for treated water and the system was also supplying irrigation water with high turbidity, the meters didn’t work properly.

The city tried to meter again before 2020, he says, but materials were delayed, arriving when they were already moving ahead with the decommissioning.

Now, Wightman says they’re just waiting for the province’s approval to do work on the NCIS, which is required for any work in waterways. To keep the decommission ball rolling, workers have begun salvaging materials that could be used elsewhere in the city, he says.

There’s now a peninsula in the river, and the flow approaches the intake straight on. In the last year-and-a-half, 23 metres of bank eroded, prompting the city to ask the province for permission to work on the bank earlier this year.

Before the province had a chance to review the request, high water flows in the North Thompson from the spring freshet forced the city to declare a state of emergency to install riprap — strategic rock placement — to help stabilize the bank.

Another reason the system has to be decommissioned, Wightman says, is that the intake and riprap have altered the course of the North Thompson River, and need to come out.

“We can’t create a negative impact to upstream or downstream properties by doing any erosion protection,” Wightman says. ”That’s the issue that’s stopped us from doing anything meaningful there.

“You can put riprap around the infrastructure, but in doing that, you have to look at the impacts that will cause upstream and downstream and if that has any chance of creating a negative impact to other properties, then the ministry will not approve it.”

The goal is to return the river to its natural flow. “There will be continued erosion there, but the goal is to get it back to what it’s trying to naturally do.”

In response to questions from The Wren about the NCIS, the province stated in an email it has assisted the city in installing the emergency riprap and would “continue supporting the city as they determine if they want to keep the riprap permanently.”

While the city is responsible for complying with applicable legislation, the province added, “There is currently no requirement for the City of Kamloops to remove the emergency works.”

The City of Kamloops has jurisdiction over the NCIS as well as “the responsibility for determining the future of water service for residents.”

The City of Kamloops did not respond to The Wren’s request for further clarification ahead of publication.

Drilling for Water

The price is steep for farmers who try to get water without the Noble Creek Irrigation System, and the idea of having no irrigation water is falling heavily on the shoulders of residents.

After this year’s devastating fire season, Debra McBride told The Wren fires are a concern for her and the farm. She still remembers watching the Strawberry Hill fire across the river progress down the hill, fuelled by dry sagebrush back in 2003.

While most users were aware of the instability and neglect plaguing the irrigation system, the McBrides, who live in a landlocked area between Westsyde Road and Crown land, were under the impression they had until 2028 before the system was shut down.

This timeline was promised by council in 2022, but in mid-June, they were informed that the system was actually being turned off this year.

The McBrides shared many different agricultural pursuits over the years: egg-laying hens, sheep, pigs, turkeys, a lush vegetable garden and fruit trees. The loss of water would drastically change their farm.

They wouldn’t be able to water any of their green areas, including an upper pasture, the only land between their house and the extremely dry grasslands that make up the Crown land they border with. The wildland-urban interface — where residential homes mingle with wilderness — has been identified by the city as posing a wildfire threat.

She and her husband Trevor ultimately decided it was better to know if they had access to water on the farm and chose to drill a well.

The truck arrived on a grey day. It was a good time to drill, she was told. If you can hit water after a drought-filled summer, you know you’ve got a good source.

“Everything was going well,” she explained. They hit gravel and mud and were expecting to hit gravel next. The water would settle under the gravel, McBride was told. Instead, they hit bedrock. There was no water.

That was it. The McBride’s $14,800 well was dry. Just a few hundred yards across the street to the left and the right, two neighbours have successfully drilled wells. You can see them from the McBride’s driveway.

On Aug. 15, NCIS users got their first chance to talk to council after months of closed meetings. Users voiced their concerns, hopes and ideas for the system over nine hours of discussion.

During this meeting, residents who use the NCIS asked for greater transparency around NCIS decisions, as many took place behind closed doors.

“It really just felt like decrees from above,” Lapointe says. “Every other decision that’s been made has been made in closed council meetings.”

They also asked for more time to organize for a future without the irrigation system.

The city responded with a new reason for the decommission. It wasn’t because the NCIS was poorly funded, as previously stated.

“It’s not the money that’s holding us back,” Wightman said. “It’s not the money that’s got us in this situation. It’s the inability to get the project permitted.”

Near the end of the marathon of discourse, one important question ultimately went unanswered:

“At the end of the day, do you support agriculture?” demanded Debbie Woodward, whose family has two agriculture businesses in Noble Creek.

What’s the city proposing?

In response to the users’ request for more time, council directed staff to explore a temporary pumping option for 2024, while still moving ahead with the decommissioning.

Kamloops farmers are used to adapting to extreme weather, climate change and overall uncertainty. Many of their frustrations stem from a lack of consultation, they say.

Lapointe notes a 2019 contractor report on the Noble Creek Irrigation System presented during a closed council meeting. She says users later found out the $14 million price was based on the assumption that users could only accept the system shutting down for 15 minutes at a time.

“We, as a community, came together and said ‘Well, no actually, realistically we can go for four days without water.’”

More recently, farmers say they received less than 24-hours’ notice to provide feedback ahead of the Sept. 5 council meeting, when decommissioning was voted through.

At the end of October, decommissioning packages were mailed out. Users were sent an offer of payment in exchange for release and settlement, alongside an explanation of the process.

Users will receive between $5,000 and $250,000 based on the amount of irrigable land they are currently billed for.

The overall estimated cost of the decommissioning payout program is $3.2 million. To help pay for this and other infrastructure improvements, residents will be paying 63 per cent more for water utilities over the next five years.

Whether the decommission payouts are enough to fund irrigation solutions for individual properties remains to be seen.

City moves ahead on temporary pump

On Nov. 7, Wightman presented a report to council on the Noble Creek Irrigation System that included a proof of concept for a temporary pumping system prepared by Urban Systems.

Building a temporary system for next year’s irrigation season would be “challenging, but is feasible” the report states.

The preliminary budget suggests the system could cost $689,500. The total includes a 10 per cent buffer for city costs, as well as a 25 per cent contingency.

After a lengthy discussion, mayor and council voted to cover 75 per cent of the cost of the temporary pump with the city’s water utility rates and for NCIS users to pay for the remaining 25 per cent, which would double what they pay now.

The final cost to users won’t be known until the project’s budget is published. That won’t happen until the project goes through a request for proposal (RFP) to select a contractor. The project was posted to the RFP portal on Dec. 4.

To calculate costs, the city also needs to determine quickly how many users would use the system. Users will still be asked if they’re willing to pay for a quarter of the cost ahead of the final total being known.

Looking for solutions

Danielle Wegelin lives on Dairy Road, which is home to many farmers on the Noble Creek Irrigation System. She had to leave the lengthy August meeting early to take care of her farm. Wegelin grows produce and hay. She’s also proactive, and when it began to look like the city wanted to decommission the NCIS back in 2018, she looked into alternate ways of farming that might use less water.

Last year, she attempted to dryland farm her 12 acres of hay, which meant only using rainwater. It’s a technique used by her Alberta ranching family.

She got one crop off during the rainy year, but it was less than half of what she got the year before using irrigation.

She tried again this year. “It wasn’t even worth me pulling my farming equipment out this year,” she says, estimating she might have gotten 20 bales. With irrigation, her lowest yield was 634 bales; her record is 900.

She has also worked on making a tighter garden layout that would still yield the same amount of produce.

However, trying to use less water ultimately worked against her. On a call with BC Assessment to determine the paperwork needed to support her property’s farm status, she discovered the rules for growing in smaller spaces are more rigorous. At two acres or more, you need to hit $2,500 of profit, but if you’re farming on less than that, it’s $10,000.

“We’re having to decide right now whether or not it’s actually feasible to maintain our farm status,” she says. “If we don’t maintain our farm status, then our taxes almost triple. It’s like getting caught in a catch-22 that I feel like I didn’t have anything to do with.”

Along Dairy Road, about a kilometre from the McBrides and next door to Dudy’s massive vegetable patch, Tricia Sullivan is eating breakfast on a Friday morning after feeding 400 chickens.

The 70-year-old has worked on the land for 18 years. She’s raised chickens, turkeys and goats, and grown her own hay. She also maintains a backyard garden that keeps her family fed, plus some extras for the neighbours and the food bank.

Sullivan worries that if the city gives up its water licence without a transition plan in place, then users will lose the licence’s historical status. Under the “first in time, first in right” rule during times of drought and water-use restrictions, the province allows those with earlier licences to continue to use their irrigation source.

It’s something farmers in Westwold, B.C., just south of Kamloops, discovered this summer when the province declared a water restriction using a section of the Water Sustainability Act.

However, only users who hook up to the North Thompson River will be eligible to receive a portion of that historical licence, Wightman says.

Many other users are worried about the value of their farms, let alone their farm status — the NCIS users are both in the Agricultural Land Reserve as well as the City of Kamloops. Without a known irrigation source, Lapointe says her partner is worried he may be “passing on a millstone” to his children.

What’s the way forward for farmers who use the Noble Creek Irrigation System?

Users are now at the end of the road. While there were some last-minute pitches, like one suggestion to move the intake over to the Tournament Capital Ranch on the other side of the river, the decommissioning is moving ahead, and quickly.

With winter setting in, Wegelin had to make a decision about next season’s bounty without a known irrigation source.

In Sullivan’s garden, there are a handful of rain barrels. She’s thankful they were full when she needed them for her garden during a sudden NCIS shut-down this summer.

At 70, she’s worried about the transition plan for her farm. A young family has shown interest, but without an established water source, it’s hard to sell a farm.

Noble Creek Irrigation System users know of two neighbours who have tried to drill wells, and come up dry. People are nervous.

Many of the NCIS users chose the lifestyle: the early mornings and late nights; the commitment and sheer work involved.

“It feels like we’re being discounted, feels like nobody really cares,” Wegelin says. “I’m a small farmer. I don’t make a lot. It’s kind of a lifestyle thing, but I grow wicked garlic that people love to buy.

“I don’t know if I want to be on my hands and knees in cold, fall-weather soil, planting garlic for eight hours a day for two weeks straight…if I’m gonna just cause more headaches for myself when it comes to watering the garlic.”

The McBrides worked their whole lives with jobs off the farm, as well as chores around the property and now that they’re retired, just want to enjoy their land.

“It keeps you active, keeps you healthy,” she says, “and the thought of moving, we just don’t know where we would want to go.”

They want to find a solution to the water problem, because not having water simply isn’t an option.

Dudy is among those motivated to find a solution. He’s a “silver-linings kind of guy.” Either that, he says, or the for sale sign goes up.

So do we. That’s why we spend more time, more money and place more care into reporting each story. Your financial contributions, big and small, make these stories possible. Will you become a monthly supporter today?

If you've read this far, you value in-depth community news