Content warning: This story mentions overdose, substance use, the toxic drug crisis and death. Please read with care. To connect with your local mental health or substance use centre, call 310-MHSU (6478).

Local interest in involuntary treatment seemed to be triggered after a 2022 article by CBC News raised concerns about people leaving court-ordered substance use treatment in Logan Lake, about 70 kilometres southwest of Kamloops.

Executive director of VisionQuest Society, Megan Worley, commented to CBC, “we’re not a jail. If they choose to leave, we can’t stop them.”

Unlike a jail, a recovery program is not legally allowed to restrain people. Staffed by frontline workers and advocates, these services do not have the physical means to stop someone from leaving.

Under B.C. law, every adult capable of understanding applicable information has the right to give or refuse consent to health care for any reason, even if the refusal will result in death.

Worley later told Kamloops This Week that if clients, including those who are referred by corrections, want to leave, “we will spend quite a bit of time working with them and trying to get them to change their minds, but we can’t physically restrain them.”

“We cannot compel people into healing from this disorder any more than we can force someone with a different diagnosis into treatment; it simply doesn’t work,” she continued.

Sean Marshall, executive director of Blue House Recovery, points to the Portuguese model, the historic 2001 drug policy reform that decriminalized possession of all drugs for personal use.

Instead of incarceration, individuals are connected to free and confidential treatment programs, including counselling, detox, in-patient, and access to harm reduction, like supervised consumption sites and needle exchanges.

Viewing addiction as a public health issue instead of a criminal one, alongside investments in public health measures like opioid substitution therapy, saves lives. HIV diagnoses caused by substance use via injection decreased by 90 per cent and deaths caused by drug use significantly decreased.

Marshall agrees this health-care centred approach is more helpful than a coercive one.

“It’s just not conducive to getting better or receiving help if you’re forcing somebody to get that help,” he says. “The chances of long term success are probably pretty slim.”

“How well does it work when we try to force anybody to do anything?” echoes Siân Lewis, executive director of the local detox centre Day One Society. “How is it helpful to force somebody to do something that they see no value in?”

Lack of evidence to support involuntary treatment

As a mother to a son who struggled with addiction and died from an overdose of the unregulated drug kratom in 2021, Troylana Manson empathises with people who want to help their loved ones.

But as an advocate with Moms Stop the Harm, she is adamant that forcing people to embark on the long journey to recovery in a specific way is counterproductive and paternalistic.

“We have to be careful, even when we’re speaking against involuntary care, that our opinions don’t get in the way and that we really do take a look at the research and the evidence that points to, mostly, that [involuntary treatment] does more harm than good.”

Involuntary treatment for substance use disorders has not proven to work better than voluntary treatment, and some research shows the health outcomes are worse. It can also increase a person’s risk of overdose and death when they leave.

These concerns, among many others, have led to organisations like the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA) to warn against the expansion of involuntary treatment.

“The reality is that we are already relying heavily on involuntary care without really examining whether it is effective,” CHMA B.C. wrote in a statement during the B.C. election.

Evidence is also lacking when it comes to recovery programs. Substance-use treatment is not regulated or standardized in the province, and treatment outcomes for centres like Kamloops’ Blue House are not tracked or reported.

There is a big difference between a recovery centre that offers volunteer-based 12-step programming, Manson says, compared to a recovery centre that offers intensive personalised health care like counselling, trauma therapy and support with employment and education.

There is also the question of how the healthcare system could support involuntary treatment when that help isn’t always available for people who want it, advocates say.

“This becomes a reinforcing negative cycle. If people can’t get services when they ask for help, their health may worsen until they are in a crisis,” writes the advocacy group Health Justice who have been pushing for an independent review of the Mental Health Act in B.C., which governs the use of involuntary care.

There is a “complete lack,” of recovery resources across the province, Marshall says, and Kamloops is no different.

“If somebody says today that they want help coming off drugs or alcohol, the first step is a detox program called Day One Society. And at any given time, there’s a 10 to 14 day wait to get into detox.”

“People are literally dying in the time it takes to get that help.”

In the case of Manson’s son Aaron, who was 26 years old when he died from toxic drugs, it was important for him to have agency over his own health.

“Unless he thought it was a good idea, he wasn’t going to go,” she recalls. “And there were a couple of times he came close to wanting to try [a recovery program], but one of the things that he feared was the disconnection.”

Because he had solid connections through school and friends, Manson supported and encouraged her son to see a counsellor regularly, rather than a residential treatment centre. “I truly believe he was almost there. If it wasn’t for him not knowing how to take that drug [kratom], he’d still be here working on his recovery.”

“I think that if we are able to help these individuals move slowly, forward in a safe way, then that’s what’s going to help deal with those problems,” she said.

To keep people safer as they recover in a way that works for them, a regulated supply of drugs is what’s most urgently needed, she adds.

“When we go down involuntary care, we need to understand we’re taking people’s right to do and see. And we have to tread super light on that.”

Is involuntary addiction treatment a violation of human rights?

Lewis and Marshall point to the Mental Health Act, which sets out the rules and limitations for individuals who are involuntarily detained in the province for mental health treatment.

Under this act, a person can be involuntarily admitted for psychiatric treatment to “prevent substantial mental or physical deterioration” of themselves or others.

To be held under the act, a doctor or nurse practitioner must complete a medical assessment and issue a certificate to hold a person for up to 48 hours to make determinations about next steps. A second certificate is needed to continue holding a person for up to one month.

Mandated mental health treatment under the act is restricted to designated mental health facilities — about 70 across the province — and in extreme cases, individuals can be recertified to receive additional mandated medical care for longer periods of time, even indefinitely.

People with a mental health disorder who have come into contact with the law may be referred by the courts to receive assessment or treatment through what’s called Forensic Psychiatric Services.

Lewis explains that substance use disorder could fall under the Mental Health Act, as it is a recognized mental health diagnosis. However, being certified under the Mental Health Act involves a series of requirements beyond simply having a severe substance use disorder.

A person must have a psychiatric disorder that impairs their ability to function and associate with others and they “cannot suitably be admitted as a voluntary patient.”

Only when a series of criteria are met can psychiatric treatments be given without a person’s consent.

These protections are in place because everyone in Canada has a fundamental Charter-protected right to “control our bodily integrity,” writes B.C. ombudsperson Jay Chalke in the introduction of the 2019 report on protecting the rights of involuntary patients.

“Because these human rights are so fundamental, there are only a few circumstances where these liberties, that are so critical to the core of who we are, can be removed by the state.”

B.C. is the only place in Canada where everyone with involuntary status is “deemed” to consent to all forms of psychiatric treatment, and this aspect of B.C.’s Mental Health Act is the subject of a constitutional challenge launched by the Council of Canadians with Disabilities that is currently in the courts.

“Once you are civilly committed under our legislation you have no right to refuse treatment,” explains Dr. Isabel Grant, professor at the Allard School of Law specialising in criminal law.

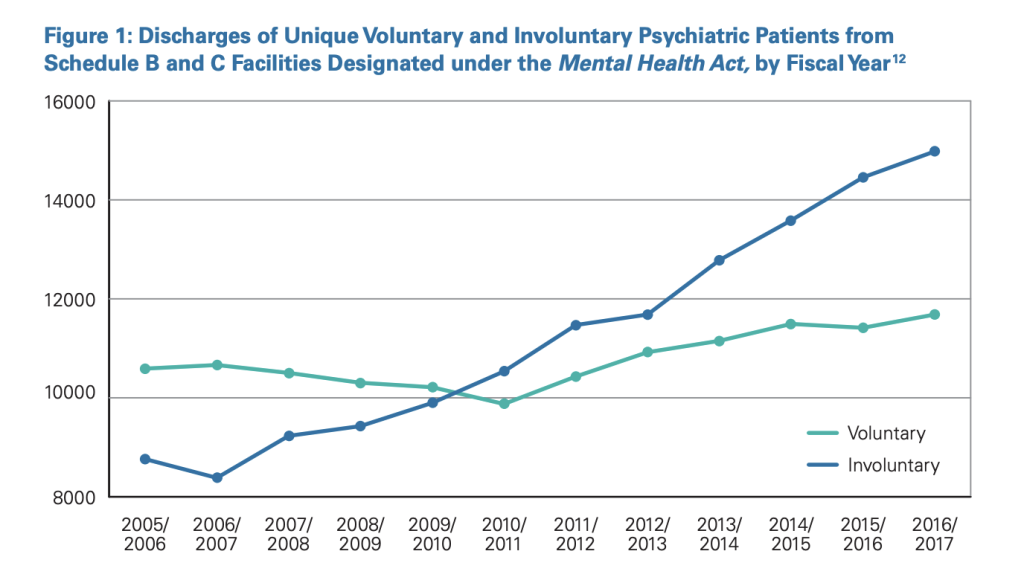

As the CMHA explains in a statement released on Sept. 18, “People with substance use disorder are the fastest growing population being detained under BC’s Mental Health Act.”

About 20,000 people are held under the act each year — a figure that is on the rise.

“The Mental Health Act allows for involuntary psychiatric treatment, but it doesn’t define the scope of that term,” explains Kim Mackenzie, director of policy at CMHA BC. “We actually don’t have very good information about what actually happens when someone is currently detained under the Mental Health Act with a substance disorder.”

Research shows that human rights violations may be occurring during detention and involuntary treatment in BC., such as an inappropriate use of restraints, seclusion rooms and sedation.

Concerns like these led the ombudsperson of B.C. to conduct an independent review of government practices in 2019.

The review found that most health care agencies were not following the reporting requirements required by law when treating people involuntarily. “The lack of documentation raises questions about whether individuals at their most vulnerable have been detained lawfully and fairly,” the ombudsperson wrote.

“Twenty-five years ago, our report Listening: A Review of Riverview Hospital expressed similar concerns about the lack of independent rights protections. A quarter century later, that gap still exists.”

The ombudsperson made 24 recommendations, many of them centred around increased oversight and accountability. For example, it suggests an independent rights advisor should be created to assist involuntary patients in navigating their rights, like accessing a second opinion regarding treatment.

In 2022, the ombudsperson confirmed eight of the 24 recommendations had been implemented. The recommended Independent Rights Advice Service was launched in 2023 with support from the CMHA.

As Lewis helps put into perspective, except under the most extreme circumstances, it becomes a violation of individual rights to forcibly confine someone to a treatment facility, regardless of if they use drugs or not.

“There are almost a million people today in B.C. who experience a mental illness or substance use disorder, and we know the overwhelming majority of them are not violent,” Mackenzie says.

About three per cent of violence can be attributed to mental illnesses and seven per cent of violence can be attributed to substance use. People with these disorders are more likely to be victims of violence than the overall population.

“There is a very small number of folks who are at a higher risk of violence, but that higher risk of violence is really a result of the system that has been unable to support them,” Mackenzie says.

Involuntary treatment for this small number of people should be used as a “last resort,” she adds. “There’s so much that we can do before we get to that point.”

Without forcing, what can we do to support people with addictions?

As a retired teacher and organizer with Moms Stop the Harm, Manson mentors people through recovery. Her approach is to ask them for what they need that day and that week, because needs are always changing and it can be extremely hard to access resources.

“I know that there are situations that are very hard to deal with, certainly youth. But we don’t have the supports in place to support them on a voluntary basis,” Manson says.

One day it might be withdrawal management, she explains. Another day it might be a place to stay that night. Along the journey, they might need help accessing and completing education, a healing journey that she credits her son Aaron for embarking on in the lead-up to his death.

“I don’t have any authority over their lives. What I do have authority over is my connection with them,” she says. “Talk about what they’re needing: What do you need right now? Where? What are you doing this afternoon?”

“When you have no authority over people, you have to address them like they’re your colleague … offer a chance for them to to feel good with you,” Manson says. “And then, from that, build some trust, and then more conversations happen to go forward.”

So do we. That’s why we spend more time, more money and place more care into reporting each story. Your financial contributions, big and small, make these stories possible. Will you become a monthly supporter today?

If you've read this far, you value in-depth community news