This story is one of five in The Wren’s email series, History at the Confluence: A glimpse into Tk’emlúps’ past.

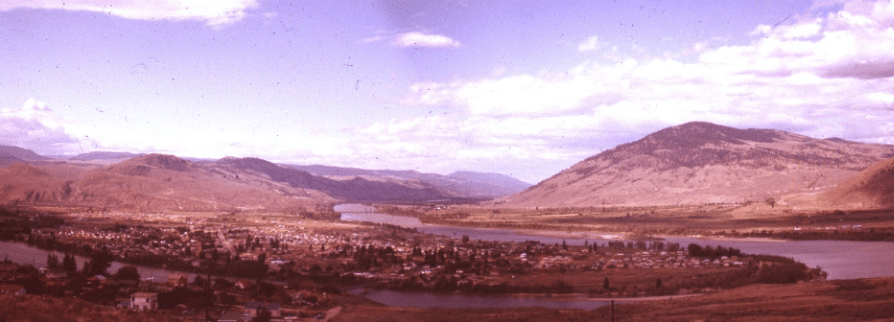

The Hudson’s Bay Company has long been recognized for its role in Kamloops (Tk’emlúps) settlement, but have you ever heard of B.C. Fruitlands? Or how the North Shore communities of Brocklehurst, Westsyde and North Kamloops grew out of this semi-forgotten company?

This is the tale of a peninsula transformed by irrigation.

The Eccentric Mr. Brocklehurst

In the early years of colonization, limited availability of irrigation water and seasonal flooding meant only a handful of farms were started on the northwestern shore of the Thompson River confluence — what we call the North Shore.

Of the few early colonists, Earnest “Ed” Brocklehurst was perhaps the most memorable.

Ed was a “remittance man” — what we might call a trust fund baby today — sent to the colonies in the late 1800s by his upper-crust English family to spare them the embarrassment of his eccentric behaviour.

It did not take long for him to become a notorious local character.

At a day of sports and picnicking held to honour Queen Victoria’s birthday, Ed’s horse Sunrise bolted, catching him by the legs with a rope and dragging him 400 metres “at a great rate.”

Luckily a local resident managed to stop the horse before it was able to jump the fence, thus saving Ed’s life or, as the May 26, 1898 edition of the Kamloops Standard put it: “otherwise there might have been no Mr. Brocklehurst.”

Unperturbed by his brush with death, Ed insisted on competing and, much to the pleasure of the audience, won the race.

Ed alongside his trusty pack of foxhounds was also known to lead his friends on hunts across the open expanse of the North Shore pursuing not foxes, but reportedly confused coyotes.

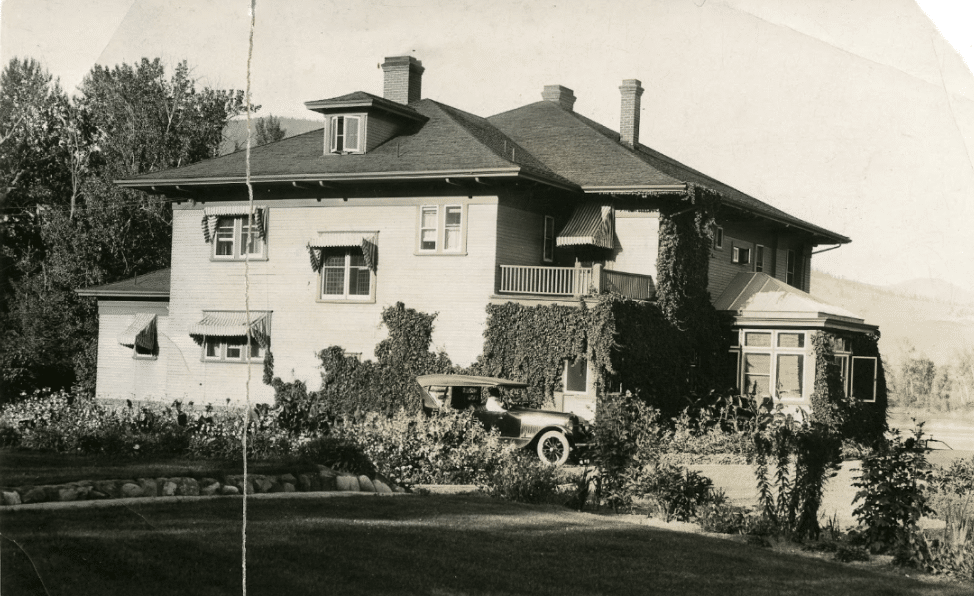

Of his luxurious mansion one resident said: “It must have been the first house between here and the North Pole to be fully equipped with an indoor bath and toilet.”

Located near the intersection of Richmond Street and Schubert Drive, the estate also featured an orchard and greenhouse.

By 1907, Ed had returned to England. Despite his short tenure in the valley, the Brocklehurst name lives on, a testament to one man’s ability to leave a lasting impression.

Oasis in the desert

After the arrival of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1898, fruit farming gained popularity in the sunny regions of the province. Though planting orchards took longer to pay off than raising cattle or grain, quality fruit commanded high prices and was a worthwhile investment in the pre-refrigeration era.

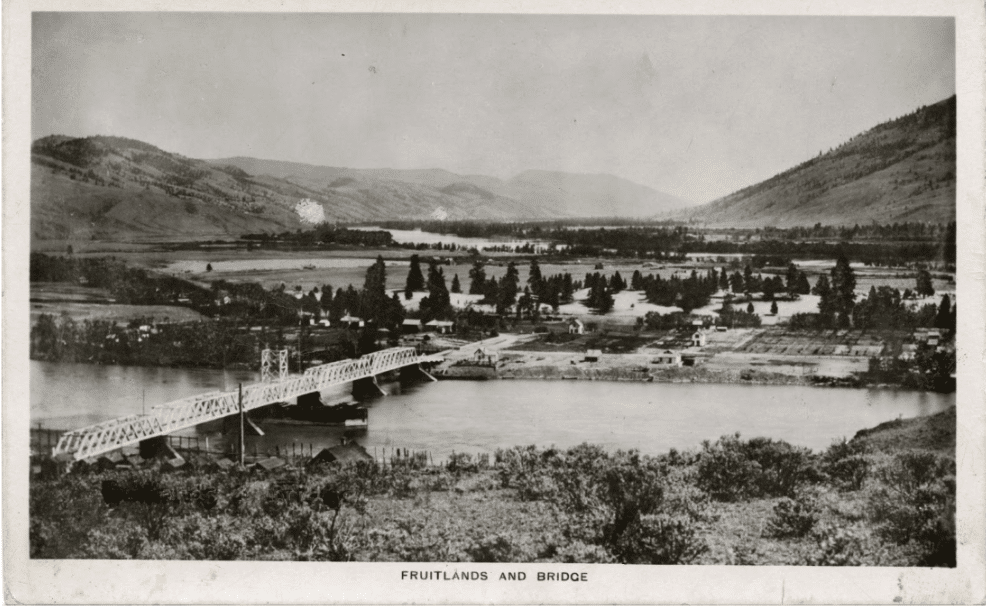

As rumours swirled that the new Canadian National Railway line would include a yard on the North Shore, a group of London-based capitalists took notice. There was wide availability of flat, low-cost land along the rail corridor. They saw the potential for a boom town to rival Kamloops, given Kamloops’ growth was limited by the South Shore’s challenging geography. All they needed was water.

In 1903, Englishman Cecil Ward on behalf of Canada Real Properties bought up land along the west shore of the North Thompson River near Jamieson Creek. The plan was to build flumes to redirect the creek for irrigation, a project that was not complete until 1905, but proved successful enough to expand operations.

The British Columbia Fruit Lands Company (B.C. Fruitlands) incorporated in England in 1909, before buying out Canada Real Properties and other title holders for a total of 2,700 Hectares of the North Shore — nine per cent of the total area of Kamloops today.

So large were their holdings that they were divided into four “blocks” for convenience, each of which roughly corresponds to a modern Kamloops neighborhood.

By 1912, B.C. Fruitlands via B.C.F. Irrigation & Power, had expanded the irrigation and power systems to all blocks.

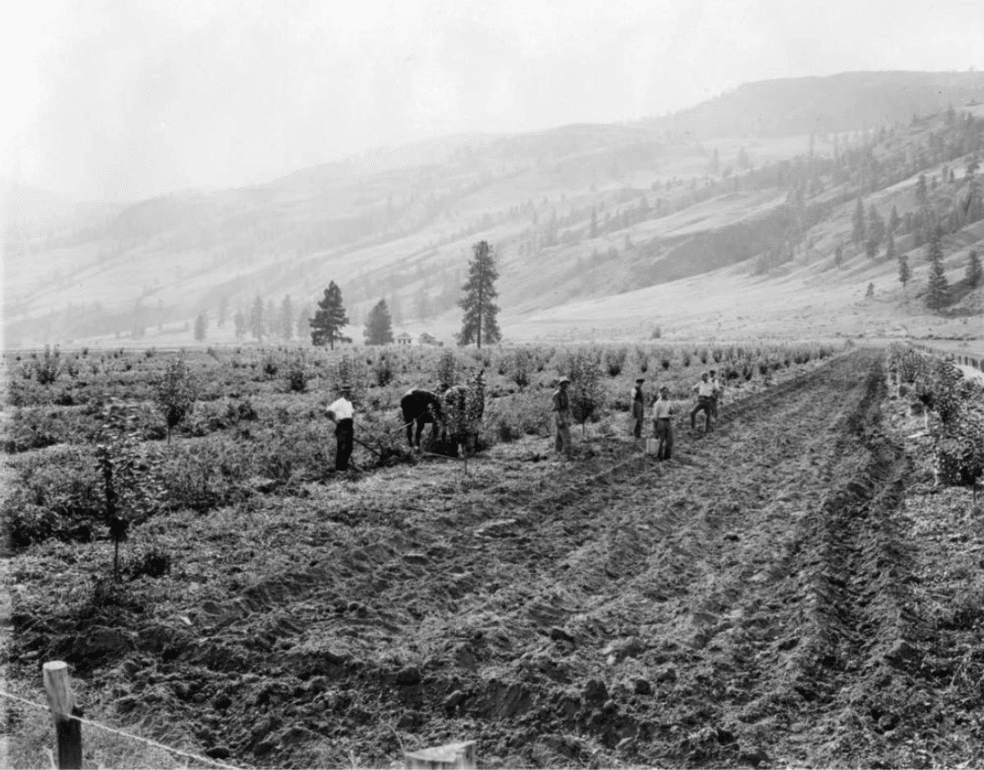

A demonstration farm run by the company, known as the “home farm,” helped diversify their investment and display the area to potential buyers. Hundreds of hectares of orchards and crops were planted and maintained by hired labourers. The manager of this operation lived at the former Brocklehurst mansion.

They advertised plots of land for sale or lease to anyone looking to farm — with B.C.F. Irrigation & Power as the sole supplier of utilities.

A February 1912 ad in Cottage Life promised “secure and profitable investments” based on their system of “scientific irrigation.” It goes on to declare “profitable results assured to men of energy and intelligence” with “only a moderate capital necessary.”

Running B.C. Fruitlands required labour, the cheaper the better. The people providing that labour came from many corners of the world: nearby First Nations, elsewhere in the British Commonwealth, Mexico, China, Japan, Scandinavia, Greece, Italy, India, Ukraine, the United States, the Caribbean and others. Some worked for only a few years before moving on while others stayed, saving up over years to lease or even buy a few acres.

North Kamloops Syndicate

In 1913, the same old boys’ club who owned the B.C. Fruitlands companies formed a third: the North Kamloops Syndicate. They sold what they saw as the best 36 hectares of Block C, everything west of the present 12th avenue, to this third company.

The idea was that property of the North Kamloops Syndicate would be subdivided into smaller, residential-sized lots and sold for a premium. This was intended to be the site of a new town, optimistically called “Wardville” after Cecil Ward by the B.C. Fruitlands owners and “Fruitlands” by everyone else.

By 1918, there were over one thousand acres being leased to farmers across the B.C. Fruitlands. However, the North Kamloops Syndicate had still not sold any of its supposedly prime real-estate. Their plans to make off like bandits didn’t work out in the end, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

Undiscouraged, B.C. Fruitlands continued to buy land, having acquired roughly 9,000 acres by 1923 including the Cherry Creek, Noble and Gordon Ranches. That same year, the irrigation system was converted to steel pipe, an improvement that cost $2 million, equivalent to about $35 million today.

The Dirty ’30s

The majority of the B.C. Fruitlands’ labourers in the 1910s and 1920s were Chinese Canadians, but by the 1930s most of them had moved to farm or work elsewhere.

Still in need of labour, B.C. Fruitlands along with the Canadian Pacific Railway and the Lutheran Church arranged to bring over some 30 families from Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, Romania and Austria. Many of these new arrivals were fleeing the rising economic and ethnic tensions in 1930s Europe and were housed in shacks along the Thompson River which had been left behind by Chinese-Canadian labourers.

They were brought as indentured labour, meaning they would have to repay their debts to their sponsors before earning wages and worked unpaid for two years. After that, they were paid $2 per day — regardless of how many hours they worked. To put this in perspective, $2 would buy roughly a side of bacon. After a few years they were offered to lease the lands they worked for a three-year contract.

The first school in Brocklehurst opened in 1930 to serve the children of these labourers. Instruction was in German, though the first priority was to teach the children English.

Teacher Anna Henschke had studied German with the dream of working on cruise lines. Instead she put this knowledge to use educating children and helping their parents integrate into the community. Her diary reveals that she frequently acted as an interpreter, eventually running a night school for parents free of charge — and unpaid — to teach English literacy.

Within two years, practically all of her pupils were speaking, reading and writing English. So great was her reputation as an instructor that three students, Amor Kam Singh and her brothers who spoke neither German nor English, were enrolled by their father specifically to be taught by Miss Henschke.

In 1937 all the students were integrated into the English language school system. At this time, shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War, many of these families were able to purchase the land they worked for $95 an acre, about half a hectare, from B.C. Fruitlands. This didn’t make the hard work any easier, but with ownership came more control over their future.

Asparagus Place and a place to belong

Meanwhile in 1922, near the present location of Bert Edwards Elementary, Sher Singh leasedeight hectares of land to farm.

Sher, born Sardar Sher Singh Heed in the Punjab province of India in 1883, had immigrated to California in 1905 as a young man. Over the years, he moved up the coast as he gained hands-on experience working in farming and logging.

He spent summers growing vegetables and winters cutting lumber for the Royal Inland Hospital. His eldest son Sucha Singh arrived in 1926 to help his father.

In 1933, Sher purchased four hectares along Tranquille Road, establishing a farm he affectionately referred to as “Asparagus Place.” His younger son Khushdev Singh joined them in 1938.

Through the 1940s, the family owned and operated Fish Lake Lumber Company as well as Punjab Lumber Company with its sawmill at Lac Le Jeune and planer mill at Halton Avenue. The Singh’s mills were recognized by the Workmen’s Compensation and Safety Board for their excellence in worker safety.

In 1942, only 12 weeks after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour, the Canadian Government ordered 21,000 people of Japanese ancestry to leave their lives in coastal British Columbia. Most were deported to internment camps in the Interior as their homes and assets were taken and sold. However exceptions to internment could be granted if an employer guaranteed a job.

Sher was that guarantor for many Japanese families. Khushdev recalled building bunkhouses on the asparagus fields to provide housing until these displaced families could establish themselves.

One such displaced citizen was Mrs. K. When interviewed in 1984, she described living in a little house on the Singh farm until 1947 when her family was able to build a new home on their own five acres.

Mrs. K stated that she “never had any problems with her neighbours” in Brock. She attributed this to the fact that they were mainly a mix of Punjabis, Germans and Ukrainians who “understood the effects of discrimination better than anyone.”

The end of B.C. Fruitlands

Despite the lofty business pitches, B.C. Fruitlands was never the cash cow its owners had envisioned. The Canadian National Railway yard ended up being built on the Kamloops Indian Reserve instead, shattering hopes of a “Wardville” boomtown.

After two decades of troubled finances, B.C. Fruitlands went into receivership in 1931, though it continued to operate. In 1946, the British Columbia Water Rights Branch stepped in, taking over B.C.F. Irrigation & Power to create the B.C. Fruitlands Irrigation District. That same year the village of North Kamloops incorporated.

It was not until 1960 that a new water system serving North Kamloops, Brock and Westsyde was finally operational, just in time for a looming population boom. But that is a story for next week.

I leave you today with the words of John Desmond, a key figure in the transition years.

“The best that can be said for the old B.C. Fruitlands Co. is that although it was badly lacking in the most elemental knowledge of what it takes to run an undertaking of such diversity — it had visualized a big future for this area.”

Further reading

B.C. Fruitlands Collection, Kamloops Museum and Archives

Brocklehurst: Fragment of the Canadian Mosaic by Irmi Hoppenrath

Kamloops, History of the District 1914-1945, Ruth Balf. Available from the TNRD library system or at the KMA reading room

Japanese Canadian Internment: Prisoners in their own Country, The Canadian Encyclopedia

Thompson Nicola Regional District Newshound Archive.

So do we. That’s why we spend more time, more money and place more care into reporting each story. Your financial contributions, big and small, make these stories possible. Will you become a monthly supporter today?

If you've read this far, you value in-depth community news