This story is one of five in The Wren’s email series, History at the Confluence: A glimpse into Tk’emlúps’ past.

On the morning of Dec. 22, 1972, the residents of Greater Kamloops were in for a surprise. As they began their days by opening newspapers or turning on radios, they were greeted by shocking news: Kamloops and the surrounding area would amalgamate and there would be no vote on the matter.

No one was told in advance — even local mayors and aldermen found out alongside citizens, from the front page of the paper.

As Dufferin alderman Margaret Cooney put it at the time when interviewed by Kamloops News Advertiser: “I think it is a poor way of doing business when you have to hear it on the news.”

By the early 1970s, the question of whether or not to amalgamate Greater Kamloops and its growing list of municipalities and unincorporated communities was raised many times, each with growing urgency.

The number of people using Kamloops’ services had ballooned and the city’s tax base failed to keep pace. Additionally, the region’s 16-or-so communities couldn’t effectively coordinate, stalling much-needed improvements, like sewer and dikes.

When North Kamloops amalgamated with Kamloops in 1967, it seemed to have galvanized opposition to unity in the other satellite communities. By the end of 1971, Valleyview, Brocklehurst and Dufferin incorporated into independent municipalities instead of joining Kamloops, as discourse between the various councils grew more hostile.

The provincial government — fed up with the infighting — decided to end the unity debate by forcing amalgamation, while stepping into a sovereignty challenge with Tk’emlúps te Secwepemc and the feds.

But why was amalgamation such a divisive issue in Kamloops? And what prompted the Province to finally step in?

Growth in all directions

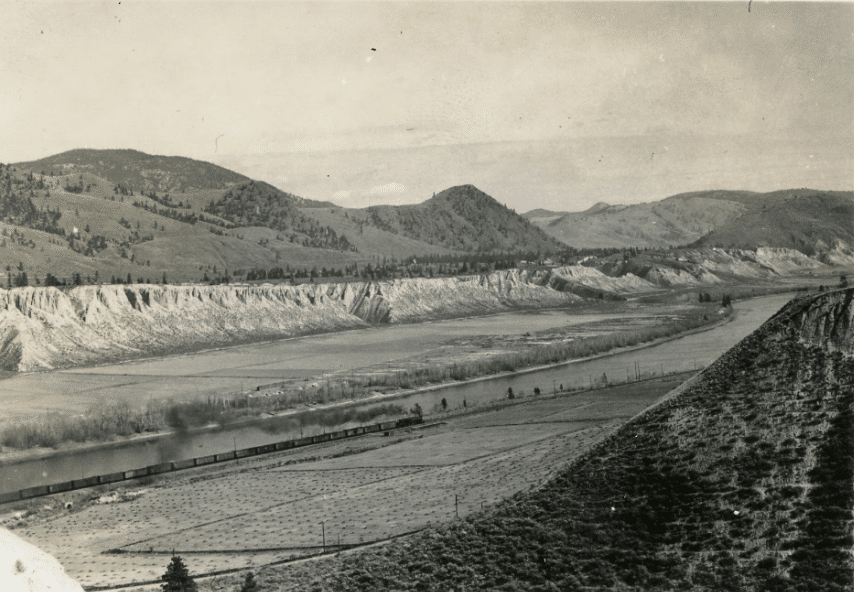

Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc was the first community at the confluence, stewarding their homelands since time immemorial until forced onto a tiny fraction of their territory, Kamloops Indian Reserve No. 1, by the colonial government in 1877.

Greater Kamloops was a catch-all term to describe communities outside of Kamloops boundaries, but still dependent on the city for commerce and services.

Beyond the Kamloops core, many rural settler communities sprung up elsewhere in the valley, including Campbell Creek, Heffley Creek, Tranquille, Knutsford, Rayleigh, Dufferin and Rose Hill. Mission Flats, as well as the Edmunds and Powers Editions bordered Kamloops to the west. North Kamloops, Brocklehurst and Westsyde emerged from B.C. Fruitlands on the North Shore. A division of Campbell Creek created Barnhartvale, and these communities to the east were joined by Dallas and Valleyview.

As the population of these communities grew, administration grew more complex. There were schools, road maintenance, fire suppression, water and power to consider and the larger the populace grew, the more services were needed.

North Kamloops was the first of these communities to become a village in 1946, upgrading to town status in 1961 when it reached a population of 6,000. North Kamloops had a population of 12,000 by the time it amalgamated with Kamloops in 1967, exceeding the city’s by 4,000.

Rather than follow North Kamloops’ lead, the other Greater Kamloops communities resisted formal organization for as long as possible.

The most cited reason was that incorporating increased tax rates. Those rates would increase further with town or city status, and opposition from prominent members of local ratepayers associations — for the most part land or business owners — grew.

No more fun and games

By the late 1960s, Greater Kamloops was in dire need of upgraded recreation facilities, water systems, sewers and dikes, as the unorganized communities had often been unable (or unwilling) to finance and administer these services alone. Each one had to negotiate service contracts independently with the City of Kamloops or each other, slowing down progress considerably.

Meanwhile the tax payers of the City of Kamloops were footing the bill for services used by residents who lived outside the city boundary.

Most residents of Greater Kamloops worked or shopped in the city limits. They commuted on city infrastructure and used Kamloops facilities like parks, pools or the library.

Despite overcrowding of recreation facilities presenting a major issue for years, projects like the expansion of the sports complex on McArthur Island were held back by a lack of cooperation from the satellite communities.

Many in the suburb communities argued their patronage at Kamloops businesses made up the taxation difference. But the city did not collect extra taxes based on these earnings.

In October 1969, Valleyview could drag its feet no longer and was incorporated into a village. Just over a year later, on New Year’s Day, 1971, it became the Town of Valleyview. Brocklehurst had grown to 8,500 residents before reluctantly incorporating into a district municipality the same year.

Likewise, the Powers and Edmonds additions (what we now call “the west end”) were incorporated with Dufferin in 1971, becoming the Municipal District of Dufferin. Lest they be forced to join Kamloops, these new municipalities set themselves to the task of proving their viability while simultaneously playing catch-up on development and pledging to keep taxes low.

The situation continued to worsen in 1972 as disputes were becoming increasingly petty.

‘Soak hills’

That spring, as a late snow pack was hit with summer-like temperatures, the water level of the Thompson Rivers rose and residents faced the consequences of infrastructure improvement delays.

On June 2 1972, the dike protecting the brand new Oak Hills residential development failed, flooding the entire subdivision in minutes, earning it the nickname “soak hills.” In a show of unity, residents from across Greater Kamloops rushed over with boats and equipment to help. A hundred or so people were pulled from the floodwaters by rescuers.

Though no one was killed in the disaster, more than 600 people were left homeless. Repairing the damage to the dike alone cost millions of dollars.

In Brocklehurst, collapsing dikes were shored up by volunteers with only minimal damage to a few homes, but seepage from the rising water table remained a major threat. Many fields became swamps, roads buckled and storm drains in North Kamloops backed up into the streets. Downtown homes along River Street were saved only through exhaustive sandbagging efforts.

This disaster highlighted the dangers of regional division. Residents were growing tired of the disagreements and in some places, the pendulum of public opinion was swinging toward amalgamation.

Two weeks after the flood, Westsyde held its second incorporation referendum, and while voters chose not to incorporate, many said they would have voted yes to amalgamation with Kamloops if that had been an option.

“I think the situation is disastrous,” said Westsyde resident, Diane Whiston. “For amalgamation I would have voted ‘yes’ yesterday. Anybody would be a fool not to.”

Winds of change

Greater Kamloops was not the only fractured urban centre at the time — with 90 per cent of British Columbia living in unorganized communities, much of the province was embroiled in similar games of incorporation-or-amalgamation hot potato.

After the New Democratic Party defeated the Social Credit Party in the August 1972 election, regional unity was at the top of the new government’s priority list.

“If one area is self-supporting and not leeching off an immediate neighbour, it is up to the people to decide whether there should be a union or not,” said municipal affairs minister James Lorimer before a visit to meet with Greater Kamloops’ four mayors and twenty two alderman. “But the practice of freeloading, of one area living off the avails of another, must end.”

It was clear by the end of 1972 the status quo could not continue and the City of Kamloops was ready to play hard ball with the outlying communities. If they wanted to go it alone, so be it.

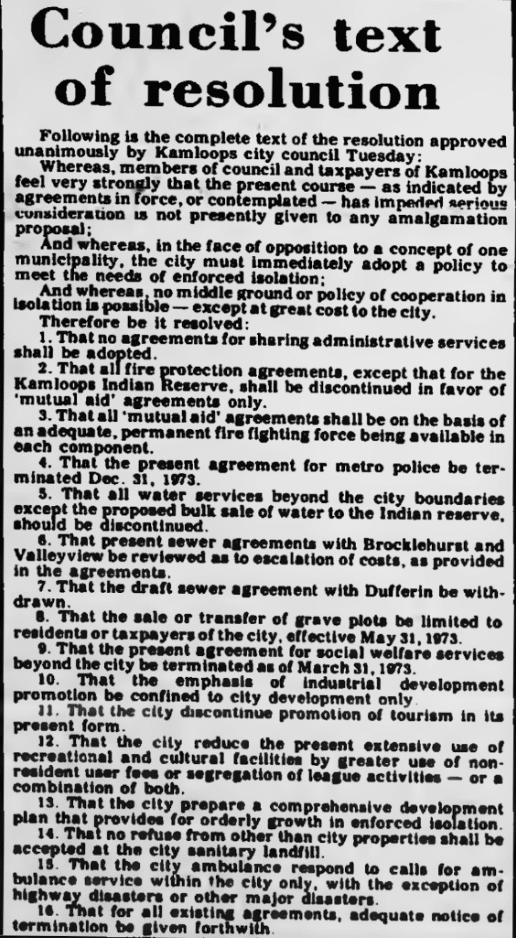

On Dec. 5, 1972 council unanimously passed a resolution to severely cut back services to surrounding municipalities and their residents, including axing ambulance service outside of city limits, restricting landfill usage and even barring non-residents from being buried in the city’s cemeteries.

Reactions to the announcement were a fresh deluge of mud-slinging by politicians, but it was favourably received by many residents across Greater Kamloops.

“As a resident of Brocklehurst, I think it’s a move in the right direction,” Noel Hunt told the Kamloops Daily Sentinel. “This will be an incentive to amalgamate the whole surrounding area. It’s a logical move by the city, and not black mail at all.”

The province steps in (and into hot water)

But the City of Kamloops was gearing up for a battle that never came to pass. On Dec. 21, Lorimier declared that all municipalities and unorganized districts within Greater Kamloops would be dissolved May 1, 1973. They would be reincorporated into one municipality under the City of Kamloops name. A committee to organize and facilitate the transition would be formed with members from across the new municipality.

The province also offered funding for projects to sweeten the pot. The deal included bringing big industrial developments like the Weyerhaeuser pulp mill, Gulf Oil refinery and Lafarge cement plant into the city limits as a major bump to tax revenue.

The announcement was not without controversial inclusions, not least the Mount Paul industrial park as well as most of the river frontage of the Kamloops Indian Reserve no.1.

While the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc were quiet about their objections to this inclusion, choosing to speak with lawyers rather than the press, there was no shortage of political commentary.

“Any plans to include a portion of the Kamloops Indian Reserve in the boundaries of the new city would have to meet with the approval of a majority of band members,” said Jack Homan, district supervisor for the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. Homan said he knew of “no legislation that would allow a province or municipality to annex reserve land without prior approval of reserve residents.”

Kamloops MP Len Marchand indicated the federal government would financially support bringing the issue to court against the province, stressing that a case like this had not yet “been tested in the courts” but would set an important precedent if it went to trial.

Getting down to business

“The amalgamation stew has had a few weeks to cool, and so have the temper tantrums,” stated Beatrice Morley, capturing the local feeling in her Jan. 19, 1973 letter in the Kamloops Sentinel.

“The purpose of this ‘shot-gun’ wedding is presumably to legitimize all us bastard offspring,” she wrote to her fellow citizens, advising that “though Mr. Lormier had his sequence reversed, I believe we should accept his invitation.”

She goes on to place blame on developers and spectators for their role in “the cancerous growth that affects this whole area,” but she reasoned “that is one of the strongest arguments in favour of some form of united community plan.”

The six-month timeline handed down by the province lit a fire under the feuding community leaders. Their attention turned from getting the smallest tax bill to getting the best deal for their neighborhood in the new plan.

It was time to get down to business, get the lawyers on retainer and get this whole “Kamloops” thing figured out.

However, there were so many lingering questions. Where would the new boundaries be placed? Would Kamloops Indian Reserve no.1 be annexed? How would taxation work? And perhaps most importantly: was any of this even legal?

Further reading

Thompson-Nicola Regional District Newshound Archive

So do we. That’s why we spend more time, more money and place more care into reporting each story. Your financial contributions, big and small, make these stories possible. Will you become a monthly supporter today?

If you've read this far, you value in-depth community news