This story is one of five in The Wren’s email series, History at the Confluence: A glimpse into Tk’emlúps’ past.

After the Colony of British Columbia was founded, it became caught in a bureaucratic paradox. Its government wanted to encourage settlers to immigrate and become tax-paying landowners, but land couldn’t be sold without first being surveyed. However, to afford surveying the vast swathes of land across B.C., the colony needed tax funding from landowners.

Their solution was to introduce an American-style policy of “pre-emption,” in 1859.

Registering a pre-emption granted the first right to purchase a plot of land up to 160 acres (about 65 hectares) before it had been surveyed. At the time of the survey, a title would be granted as long as the land had been “improved” within a set period of time, according to colonial standards, and the discounted sale price was paid. In 1861, the price was lowered to four shillings and two pence per acre. Adjusted for inflation that’s roughly $3.43 per acre ($1.40 per hectare).

Persons from First Nations were limited in how much land they could pre-empt and in 1866 were barred from pre-emption all together.

Many of the first settlers to take up pre-emption were former Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) employees, often already squatting on desirable parcels of land with their wives and growing families. They were joined in short order by newcomers from Britain, Canada, the U.S. and much further afield.

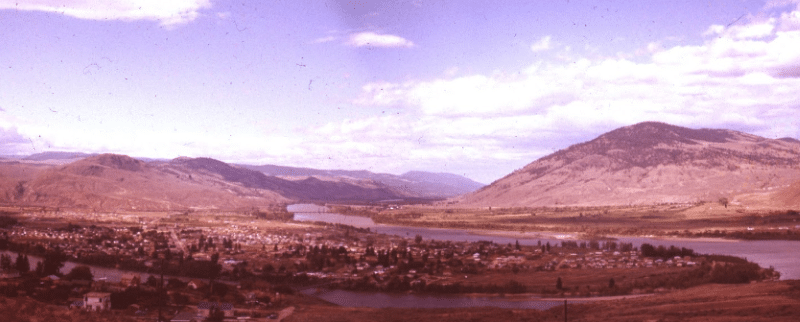

In Tk’emlúps, it was not just Kamloops that emerged. Travelling east up Secwepemcétkwe, the South Thompson River, would bring you to Campbell Creek and later, Barnhartvale — now Kamloops’ easternmost neighbourhoods. The names of streets and landmarks give us clues about the early colonists who established lives there.

At the end of a dusty trail

Rather than prospecting for themselves during the gold rush years, American business partners Lewis Campbell and John Wilson made their money by leading pack trains. These caravans of horses that carried supplies and mail were an essential lifeline for early settlers.

In 1864 the pair rode down to Oregon to invest their earnings in 300 head of cattle. They drove this herd north, wintering them at a spot east of Kamloops along the South Thompson river before delivering them to market.

It was here along the South Thompson that Lewis met the widower Jean Baptiste Leonard and his daughter Mary, who would become Lewis’s future wife. Jean and Mary took Lewis under their wing, teaching him the ins and outs of ranch life.

Jean was a former HBC employee who had pre-empted land along what would become known as Campbell Creek. Mary’s mother Alkoh, thought to be a member of the Lheidli T’enneh First Nation, died when her daughter was young. After her death, Mary moved with her father to Fort Kamloops — then a HBC trading post at the confluence of the North and South Thompson Rivers.

As Mary was reaching adulthood, Jean married Marguerite Sllortssa of Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc. The couple went on to have five children together. Their descendants include many prominent Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc members, past and present.

As her father was starting a new family with Marguerite, Mary was beginning hers with Lewis.

Lewis pre-empted land adjoining Jean’s, then wed Mary in “the custom of the country,” or what we might call common-law today. A few years later, they married again in a Catholic ceremony to ensure their children would be considered “legitimate” in the eyes of colonial society.

Mary and Lewis eventually bought Jean’s land as well. The couple worked the ranch together, building it into a successful business while growing their family by eight children. They continued to purchase surrounding land until they owned nearly one thousand acres (404 hectares) along the South Thomson waterfront.

The age of rail steams ahead

As the end of the century approached, so too did the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR).

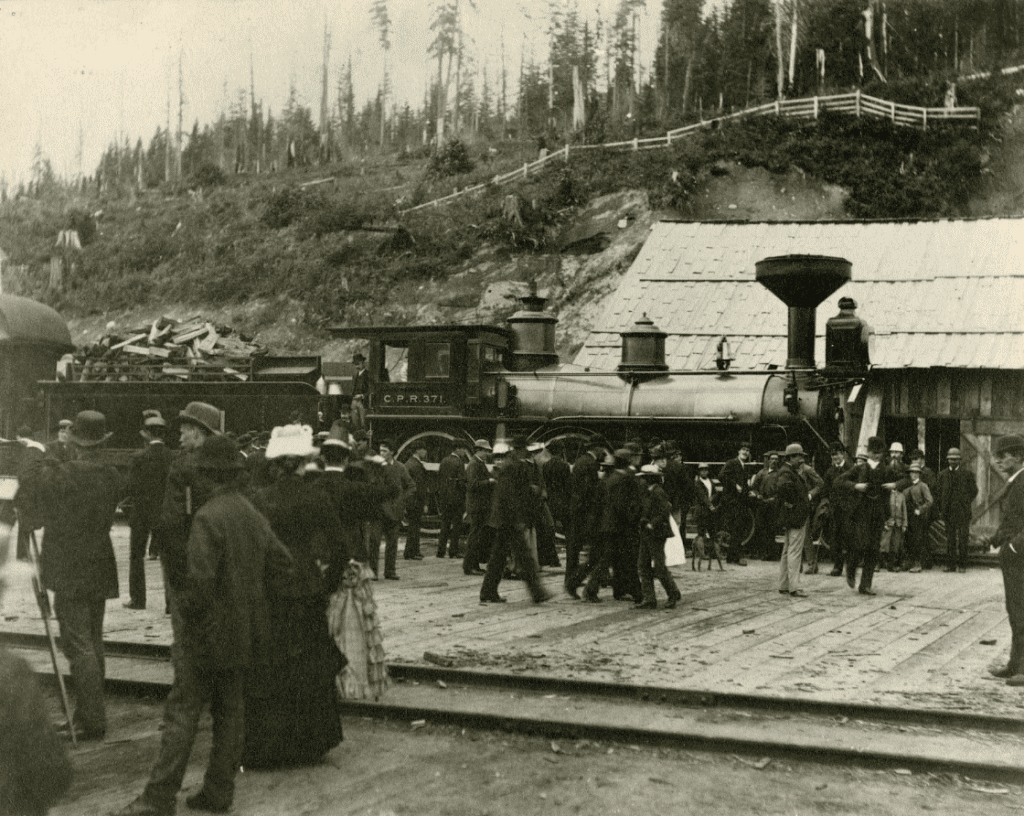

On July 3, 1886, the first transcontinental passenger train from Montreal came through Kamloops on its way to Port Moody and Vancouver. It was nearing midnight when CPR engine 371 rumbled into town, but residents still greeted the train with a celebratory bonfire. The conductor of this historic trip was named P. A. Barnhart — but more on him later.

Kerfuffle at Campbell Creek School

Schooling for their children was a top priority for the Campbells and in 1892, at their own expense, they built a one-room school at the ranch.

The family provided all of the furnishings and supplies, as well as a separate two-room house for a teacher to board free of charge, as the provincial ministry of education provided a $50 per month salary for the teacher.

Jessie McQueen, the teacher for the 1893-94 school year, wrote favourably about the post in her letters home.

“Mr. [Campbell] says he wants to do what’s right by me and I told him that many-a-one might do what’s right and still not do one-sixteenth what he does.”

She also wrote to the superintendent that “[Mr. Campbell] does everything in his power for the sake of the school.”

Though Jessie was fond of the Campbell family, she only stayed for one year. It was common at rural schools for teachers to change frequently, as the educated young women who filled these rural posts were often called away by family obligations or offers of marriage.

The Campbell Creek school teacher for 1896-97, Winifred Swan, had a sour relationship with the Campbells, refusing to eat food they supplied and disciplining students severely. The source of her dislike came to light when her cousin, a CPR official, complained on her behalf to the superintendent. He claimed, “one of the largest [students] after drinking about half a pitcher of water deliberately threw the balance in her face [which] is, as you may confess, very hard to stand from a lot of half-breeds” (a slur referring to people of mixed ancestry).

This incident was sensationalized in the press and was even discussed in the provincial legislature. The school was closed.

Not being one to back down in the face of prejudice, Lewis retorted with a firm statement to the superintendent against the CPR official: “There is not a half-breed in the school but even if there were, their rights are as much to be respected as another person’s and such slurs are unbecoming.” After an investigation cleared the Campbells of wrongdoing, the school was reopened in 1898 and remained so until low attendance forced its closure in 1926.

At the behest of local families wanting to keep their children closer to home, a second school by the name of Campbell Creek South opened in 1902. This school operated until 1956, though somewhere along the way the name was changed to Barnhart Vale School, which might give you a hint about the direction the region was headed in next.

Modern street names in Barnhartvale such as Todd, Pratt, McLeod, Pringle, Leonard and Blackwell bear the names of other notable families from this period and may as well have been plucked straight off the attendance rolls of these schools.

The many adventures of P. A. Barnhart

Peter Ashton Barnhart — who we met earlier as the conductor of that first transcontinental train in 1886 — was born in Ontario before coming west to work for CPR sometime before 1881.

Like many trainmen of the time, Barnhart eventually left CPR to explore other opportunities. Around a decade after his transcontinental train ride, Barnhart’s family entered into the hotel business, first in Mission in 1897 then in Kamloops at the Cosmopolitan Hotel the year after.

After Barnhart unsuccessfully ran for city alderman in 1904, the family bought and moved to an acreage in the south of Campbell Creek. They opened a post office in June 1905, as well as the area’s first telephone office.

The post office continued to operate under the name Campbell Creek (South) until 1909. On April 7 of that year, a notice was published in the local newspaper, the Inland Sentinel, explaining there would be a name change.

“On and after June 1 the post office at P. Barnhart’s place now known as Campbell Creek post office, will be called Barnhart Vale. This has been announced by the department in consequence of representations made through his legal adviser [sic] by L. Campbell, the well-known rancher who was suffering considerable losses owing to the mis-delivery of mail”.

And so Barnhart Vale was born, carved off of the area then known as Campbell Creek because too much mail was being delivered to the wrong place. Barnhartvale — condensed to one word by the 1970s — still exists today as a neighborhood of Kamloops.

The Barnharts did not stay in Barnhartvale very long, having returned to Kamloops — then a separate community — by the time of the 1921 census. Peter lived a long and seemingly busy life. He operated a garage, served as a city alderman and was a high ranking member of the local freemasons.

One notable event took place in 1936, on the 50th anniversary of Barnhart’s famous transcontinental trip. As part of the Vancouver Golden Jubilee, he took part in a re-enactment of the final leg of the journey. Large crowds, many dressed in 1880s fashions, gathered to watch as engine 371 pulled into the Port Moody station, which still stands today as the Port Moody museum. The procession paused for photos before proceeding on to Vancouver station for celebration and speeches.

Where the past and present meet

Lewis and Mary Campbell passed away only one year apart, in 1910 and 1911 respectively. The couple’s legacy is not forgotten as many landmarks in the area carry their name. Today, Campbell Creek is Kamloops’ easternmost neighborhood.

They were laid to rest on a little hill overlooking the family ranch. Over the decades, the community’s tiny pioneer cemetery was almost forgotten among the sweet smelling grass and sage brush, but is now guarded by a simple wooden fence. This resting place of many early 20th century settlers is nestled among the homes of Campbell Creek’s present residents.

Upon Mary’s death, the ranch was divided among the Campbells’ seven surviving children. The property was eventually converted to a hop farm before subdivided for development in the 1960s.

In 1966 a portion of the old Campbell ranch became the B.C. Wildlife Park, a beloved institution providing wildlife rehabilitation and education. Also on the park grounds, the Wildlife Express Volunteer Society operates the Wildlife Express miniature train and a number of outdoor displays celebrating B.C.’s rail history.

So the next time you take Barnhartvale Road on your way to picnic at Campbell Lake, spare a thought for the families that came before us. Their lives touch ours in more ways than we know.

Further Reading

Kamloops Cattlemen by T. Alex Bulman

The West beyond the West: a history of British Columbia by Jean Barman

Sojourning Sisters: the Lives and Letters of Jessie and Annie McQueen by Jean Barman

British Columbia in the Balance 1846-1871 by Jean Barman

So do we. That’s why we spend more time, more money and place more care into reporting each story. Your financial contributions, big and small, make these stories possible. Will you become a monthly supporter today?

If you've read this far, you value in-depth community news