Now we greet the early spring,

The flowers bloom, the birdies sing,

While nature smiles, the fields are gay,

And bids us crown you Queen of May.

– Excerpt from a 1905 poem recited by former Kamloops May Queen Violet Kyle to her successor, Mary Barnhart, published in the Kamloops Standard

There’s good, grassroots news in town! Your weekly dose of all things Kamloops (Tk’emlúps). Unsubscribe anytime.

Get The Wren’s latest stories

straight to your inbox

One-part pagan fertility festival, one-part celebration of childhood and one-part British Empire propaganda — this is the story of May Day in Kamloops.

Long ago Kamloopsians young and old celebrated the coming of spring with a civic holiday now largely forgotten.

Until just decades ago, it felt like the entire city was swept up in annual parades, youth crowned as “royals” for a day, teens dancing all night and even controversy — and high-profile resignations — over the morality of the holiday.

An ancient holiday reborn

The origins of May Day have been lost to time, predating the introduction of writing, Christianity and even the English language to England.

Celebrated on May 1 — roughly midway between spring equinox and summer solstice — the holiday shares elements with other spring festivals of the British Isles, such as Gaelic Beltane and the Welsh Calen Mai, explains the UK’s National Trust.

The day can also be traced to the Roman festival Floralia, and other mainland European spring celebrations.

The May Day of ancient and medieval times was a celebration of spring and fertility.

In many places, it was tradition to crown a Queen of May from among a community’s young women; sometimes a male counterpart was also chosen as her consort, often called Jack-the-Green or a May King.

The pair’s duty was to oversee their community’s merriment, dancing and feasting — to ensure a good time was had by all.

Heated religious debates

But despite the festival’s popularity, in 1644, British authorities banned May Day celebrations during the religious and political turmoil of the decade-long English Civil War, according to the Museum of Oxford.

At the time, protestant fundamentalists viewed dancing — a key part of most May Day celebrations historically — as an immoral public display of sexuality.

To the religious hard-liners, the Maypole — an ancient emblem of the holiday, with possible roots in ancient European pagan tree worship — was seen as idolatrous.

In town squares across England, mobs of religious extremists chopped down and burned Maypoles, some of which had stood for centuries.

After the Civil War and the king’s overthrow, societal turmoil and poor governance created strong nostalgia for the past. Average people simply yearned to celebrate the coming of spring, as they had for centuries.

They got their wish with the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. To celebrate the return of King Charles II to the British throne, many communities raised Maypoles again — including a 41-meter-tall pole at The Strand in London — creating a lasting association between May Day and loyalty to the monarchy.

Yet, heated religious debates over the holiday’s morality persisted, and in the Victorian era it shifted focus from young couples’ fertility to a product of it: their children.

A traditional Kamloops May Day

It was in this form that Kamloops’ fire brigade chief William Murrey brought May Day to the city in 1903, inspired by how the holiday had been celebrated in New Westminster since 1870 — the longest continually held in the entire Commonwealth.

When May Day arrived, the children only had morning classes before their teachers marshalled them into the parade.

In its inaugural years, the parade began at the Kamloops Musical and Athletic Association Hall on the 100 block of Victoria Street.

Participants then marched along Main Street, since renamed Victoria Street West, and across the White Bridge to Alexandra Park on the North Shore.

Starting in 1907, the parade route moved, starting from the Fire Hall, now the Kami Inn, on the 300 block of Victoria Street and ending at Riverside Park.

The May Queen — chosen by an advance vote in the schools — led the parade in a highly decorated carriage with her predecessor and their maids of honour, surrounded by an honour guard of Boy Scouts.

Following behind them were fellow students and other carriages bearing the mayor, city councillors — then called aldermen — and any honoured visitors.

After the procession arrived at the park, the girls of the May Queen’s “court” climbed a specially-built stage for the coronation ceremony, complete with thrones for the current and former May Day nobility.

In contrast to the rest of the day’s events, the ceremony seemed designed to challenge the attention spans of the children.

Civic leaders gave long speeches usually extolling the glory of the British Empire, and the superiority of the colonial way of life and its claims of offering peace, freedom and prosperity.

Such lofty rhetoric is in retrospect brutally ironic, considering the ways Great Britain violently expanded its global empire — through displacement, segregation, genocide and discrimination against anyone not a member of upper echelons of the strict ethno-economic hierarchy.

Perhaps just when impatient children in the May Day audience couldn’t endure another minute of pontification, the former May Queen ceremonially passed her duties to her successor by placing a crown of flowers on her head.

At this crowning moment the gathered crowd would cheer loudly, and the Rocky Mountain Rangers band performed the anthem God Save the King followed by either The Maple Leaf Forever or O Canada depending on the era.

Next in the program was the Maypole dance, usually performed by girls — reportedly because boys were reluctant to participate in activities they considered feminine.

In this we see one of the contradictions between May Day as a children’s festival, and its older incarnation as a fertility celebration — in which young adults seized the opportunity to show off and flirt with other eligible singles.

After the Maypole was braided in ribbons, the ever-popular concession would open and the sports competitions would begin.

In the early years, this meant races for all ages with prizes for the top three finishers.

Later, festivities grew to include folk dances, gymnastics, swinging clubs, dumbbells and more.

The night closed with a community dance at the Kamloops Agricultural Hall that once stood in Riverside Park. No adults were allowed on the dance floor unless dancing with a child.

By 11 p.m., younger children were sent home to bed so teens and adults could dance until morning.

A moral panic

While May Day was beloved by children, that rosy view wasn’t shared by all adults in Kamloops, however. Some residents bristled at having to shut businesses and services for a half day.

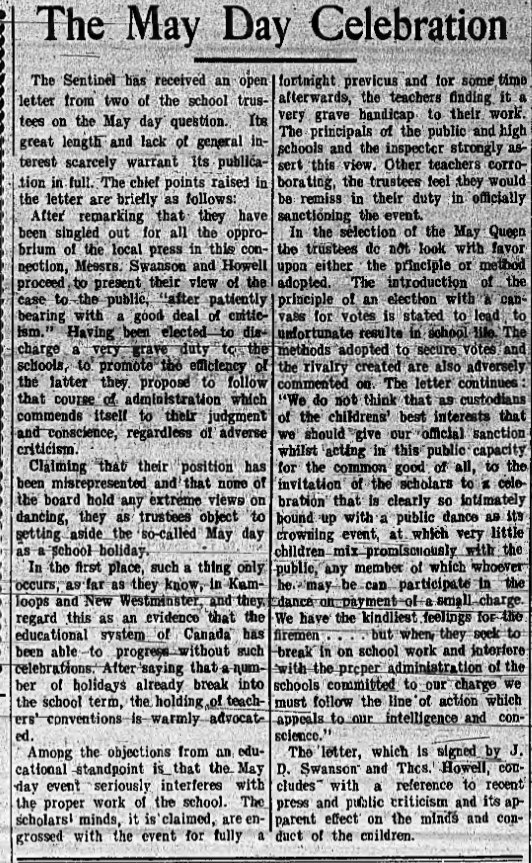

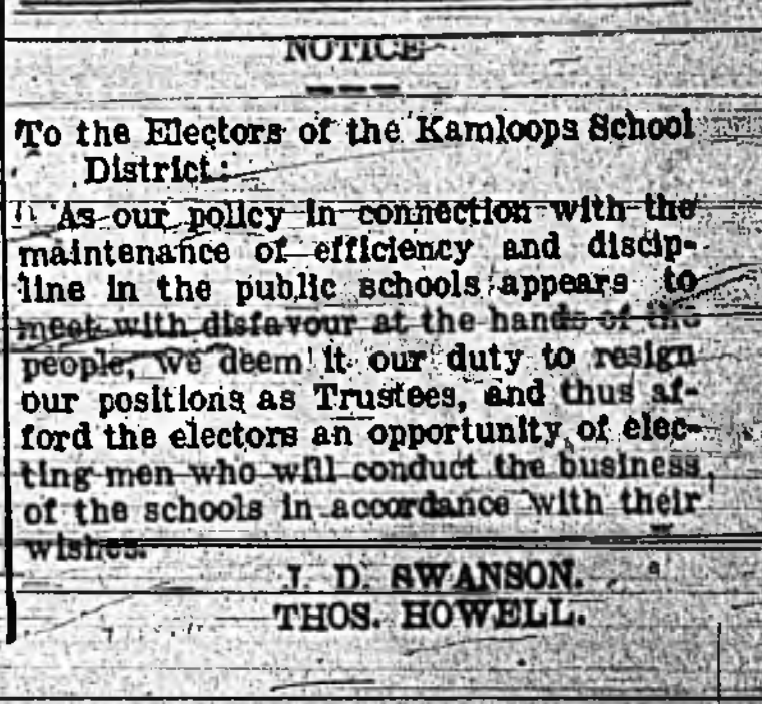

In 1908, controversy over May Day’s morality erupted when school board trustees J.D. Swanson and Thomas Howell refused to ask the education department for the necessary holiday.

The public was outraged, especially because on April 11 the Kamloops Standard newspaper reported one of the reasons as the trustees’ “personal objections to dancing.”

The Inland Sentinel published the pair’s open letter on April 21, in which they insisted they held “no extreme views on dancing” — but simply objected to a student celebration “so intimately bound up with a public dance as its crowning event, at which very little children mix promiscuously with the public.”

Ultimately, public outcry won out and May Day went ahead as planned.

For the first time ever in Kamloops, May Day made front-page news. The Inland Sentinel gave the trustees’ resignation letter merely a tiny space in the page’s bottom corner.

The threat of the beloved holiday being cancelled evidently ignited a passion in the hearts of Kamloops residents, ensuring it would remain in the canon of public holidays for decades.

The worst of times, the best of times

In 1915, a year into the First World War, the city’s May Day events featured a send-off for the Rocky Mountain Rangers, who joined the parade and played a baseball game against the high school boys’ team — before departing for the European battlefields.

During the bloody war, Kamloops’ adults sought to keep children’s spirits high, continuing the popular May Day traditions. Wounded soldiers recovering at Royal Inland Hospital and Tranquille Sanatorium attended the festivities during the war years.

Many of these war-weary young men had just years earlier been innocent participants in May Day revelry.

Wartime speeches at the events valorized sacrifice for the British Empire, but one can imagine how empty those words may have felt to those suffering most from serving in the trenches.

In the war’s aftermath — and the devastating influenza pandemic that followed in its wake — Kamloopsians hoped to put those hardships behind them.

May Day, with its focus on innocence and youthful joy, was celebrated with heightened enthusiasm.

Year-after-year headlines declared each successive May Day the finest ever.

The grandness of these celebrations was a matter of civic pride, with newspapers boasting that only Kamloops and New Westminster gave May Day its proper due in the entire Dominion of Canada.

Not to be outdone by its larger counterpart, North Kamloops began hosting its own celebration, complete with its own May Queen, Maypole dance, parade and everything else a proper May Day entailed.

By the 1920s, children did not march in the parade but were instead driven in automobiles, sometimes as many as 150 vehicles driven by members of the public.

Echoes of echoes

The golden age of Kamloops’ springtime festival would not last. In 1930, the Great Depression achieved what moral panic and the Great War could not: the cancellation of May Day.

Although it would return two years later, the festival had forever lost its lustre.

This version, hosted by the Elks of Canada, became a hybrid celebration with Empire Day, today’s Victoria Day.

Sponsors offset some of the costs but could not fix the central problem with May Day — at a certain point it became untenable to host such an event for upwards of a thousand children hopped up on sugar and exhilarated by their half-day off school.

The revival lasted only two years. But the Elks kept holding Empire Day events that included most elements of May Day celebrations and even the crowning of a queen.

In place of May Queens, the new royalty were called Carnival Queens, a tradition that continues in today’s Kamloops Ambassadors Program.

After the Second World War, May Day saw another attempt at revival which ultimately suffered the same setbacks as the previous.

A summary of the 1948 May Day events in the Kamloops Sentinel reveals the chaos of the festivities: “Enormous quantities of revels, popsicles, hot dogs and orange drink;” hordes of people trampling the park’s newly seeded grass; hot dogs running out by afternoon; and parent teacher association members serving refreshments unable to find even “a minute to breathe.”

“Gosh, I’ve eaten 18 things,” exclaimed one young boy quoted in the May 19 Kamloops Sentinel, alongside reports of dozens of lost coats, hats and even children.

This was not the end, like seeds of a springtime dandelion, the spirit of May Day dispersed, moving into the schools and merging with annual sports days

To anyone who remembers eating a jumbo freezie on track-and-field day — you may not have known it, but you were participating in that storied tradition of sports and ice cream.

Westsyde did not keep its May Day celebration confined to school hours. Instead, from the 1950s until 1972 it was a community affair hosted at Westsyde Centennial Park featuring the traditional parade, Maypole dance, sporting displays, coronation ceremony and an evening community dance.

Certainly to the disappointment of the children, also returned were the speeches from politicians of the era, for instance popular Kamloops Mayor Peter Wing, former MLA Phil Gaglardi and others.

Even this revival would not last. After a flood damaged the park in 1972, the following year’s Westsyde May Day celebration was cancelled, and never returned.

Perhaps the lesson to take from May Day’s convoluted, and sometimes controversial history in Kamloops is that, while the allure of nostalgia may be comforting, we cannot turn back the clock.

After all, no two seasons are the same, yet each new springtime represents a fresh opportunity for growth.

As 1905 Kamloops May Queen Mary Barnhart recited to her predecessor, Violet Kyle:

Another year has passed away

Since we crowned you Queen of May.

Your loving subjects will often tell

How you ruled them wise and well.

Your reign has been a rule of peace,

So may your future joys, Increase.

To another Queen this day we bow,

May sweeter laurels deck your brow.

Your future life be one of love.

Crowned by sweeter blessings from above.

So do we. That’s why we spend more time, more money and place more care into reporting each story. Your financial contributions, big and small, make these stories possible. Will you become a monthly supporter today?

If you've read this far, you value in-depth community news