In the early morning of Sept 19, the vital connection between downtown Kamloops and the Mount Paul Industrial park of Tk̓emlúps te Secwépemc reserve no. 1, known as the Red Bridge, was consumed by fire in what the RCMP suspect was an act of arson.

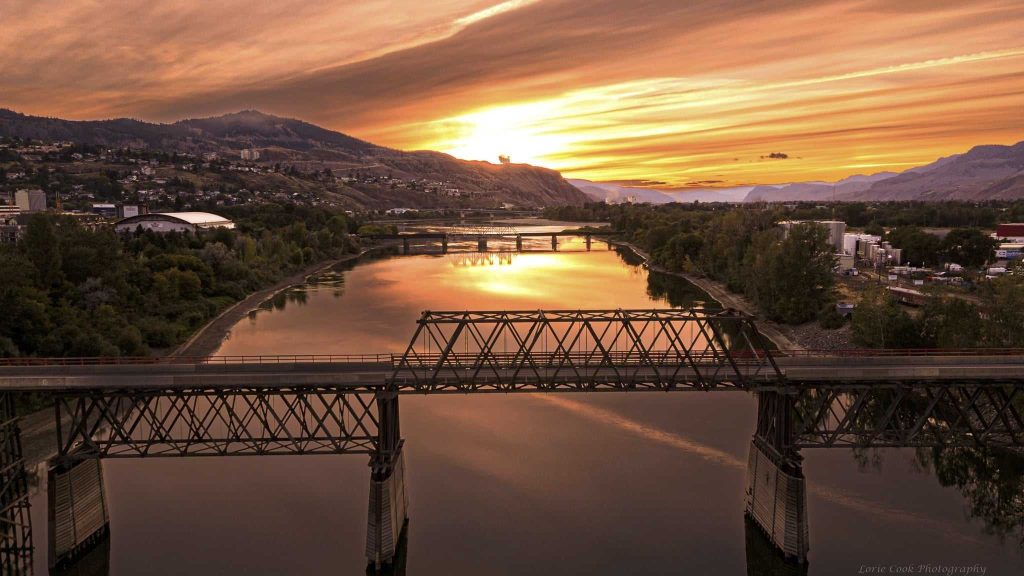

Reactions of shock, sadness and anger continue to ripple out as the community reels from this loss. The 88-year-old narrow wooden bridge, owned by the B.C. Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure, is not the only link between the two communities. But it is a central route that is “historic and culturally significant,” the City of Kamloops and Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc said in a joint statement the day of the incident.

Cleanup of the charred, creosote-treated remains of the bridge is ongoing. Many additional questions remain to be answered in the coming weeks and months, including results of the ongoing investigation, possible reconstruction and what will be done to support those who rely on this crossing.

Answers to these and many others will be revealed in time. For now, the unique history of the Red Bridge tells us why the loss is so significant.

The Red Bridge lineage

The bridge Kamloops lost last week was actually the third Red Bridge to span the South Thompson River. The first was constructed in 1887 to replace the precarious ferry crossing in the same place.

Its first official name was Government Bridge, but locals called it the East Kamloops or Red Bridge after the colour of the red cedar from which it was constructed; and so the tradition of Kamloops’ coloured bridge names was born.

It was the first bridge in Kamloops and an only child until the West Kamloops, or White Bridge, was built over the Thompson in 1901.

Red Bridge I stood for 25 years until it was replaced by Red Bridge II in 1912, using the same pilings as its predecessor.

As the population of the valley grew, so too did the traffic and resulting wear on the bridge. Damage caused by fires in 1932 and 1935 were repaired, but it became clear that the structure would have to be replaced sooner rather than later.

This iteration of the Red Bridge stood only 24 years.

Red Bridge III was constructed in 1936, slightly east of the existing bridge which was still in use while its replacement took shape.

Paul McMasters, provincial bridge foreman overseeing the job, told the Kamloops Sentinel on Oct. 6, 1936 that this structure was one of the best he had erected in years and that it “should be good for more than 30 years.”

He could not have known then that this bridge would stand for 88 years, nearly three times his estimate.

Traffic took a toll on the bridge and major maintenance was undertaken in 1970, widening the deck by six inches, adding a handrail and giving it a new red paint job.

For the first time since 1936,the Red Bridge actually painted red. New height and weight restrictions for vehicles were put in place to extend its life, given there was now a more suitable alternative in the form of the Yellowhead Highway Bridge.

A symbolic span

The Red Bridge is more than just a structure. Locals describe it as a physical representation of the link between the City of Kamloops and Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc. Though the bridge became notorious for its humps, potholes and neglected maintenance, it has been essential to both communities’ prosperity.

When the European traders, and later settlers arrived in Secwépemc’ulucw, they could not have survived without the support of their hosts. As described in the 1910 Interior Chiefs Memorial to Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Secwépemc law says that when a person enters their territory they are a guest, and must be treated hospitably as long as they show no hostile intentions. At the same time it is expected that guests return equal treatment for what they receive.

The first traders marvelled at how many dried salmon the local people would trade for simple goods, not because they did not understand their value but because they were being generous hosts. It was not only supplies but knowledge and labour that was provided by Indigenous Peoples who acted as guides, trappers, packers, carpenters, cowboys and much more as time went on.

The first bridge constructed over the South Thompson connected the nascent city to the Tk’emlúps village because early settler communities were dependent on the land, waters and resources of the unceded territory of the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc.

Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc were also increasingly reliant on their neighbours for access to rail service, foodstuffs, and other everyday goods.

Bridging the divide

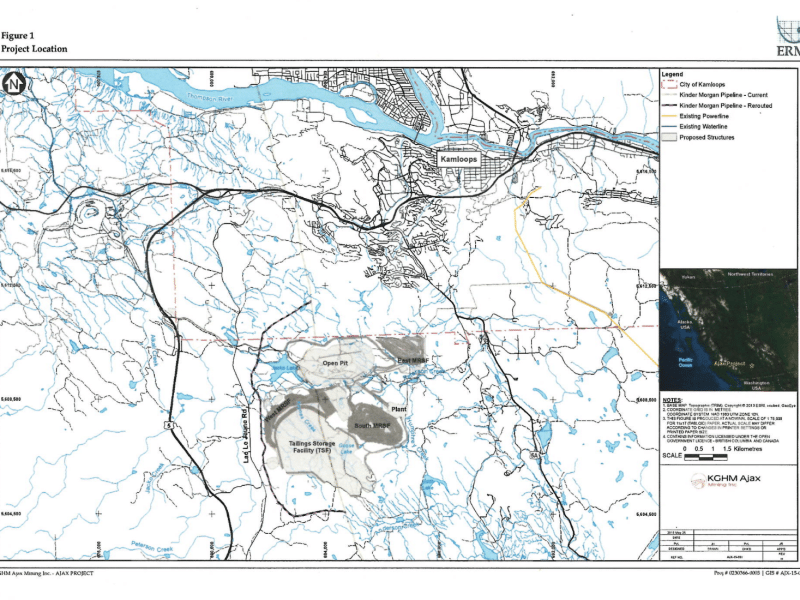

When the City of Kamloops ran out of suitable space for industry near the downtown core it was Tk’emlúps that answered the call by developing the Mt. Paul Industrial Park just across the Red Bridge from Lorne Street in 1962.

And yet, just as the city praised Tk’emlúps for the development of the industrial park, the Kamloops Daily Sentinel documented, in November 1962, both Kamloops Alderman Don Wadell’s desire to bring the industrial park into the city’s boundaries and Alderman Gene Cavazzi’s objection to that plan.

The 1970s marked a low point in this relationship, after a failed attempt to annex the Mt. Paul Industrial Park into the City of Kamloops in the late 1960s followed by its annexation by decree through the forced amalgamation of Greater Kamloops in 1971.

Tk’emlúps successfully negotiated for the return of the industrial park lands from the city in 1976.

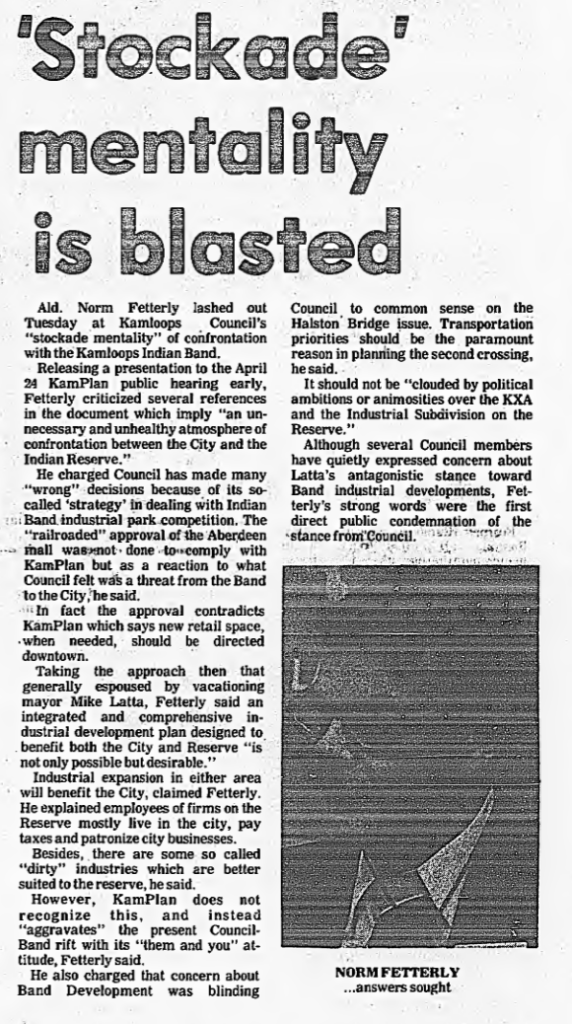

A further debate around the placement of a new bridge, the Halston Bridge, led to open hostilities between the City of Kamloops, B.C. and Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc lasting into the 1980s.

Many rights of self determination were won back from the Department of Indian Affairs during this period and Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc was determined to build on this momentum and build the future of their community.

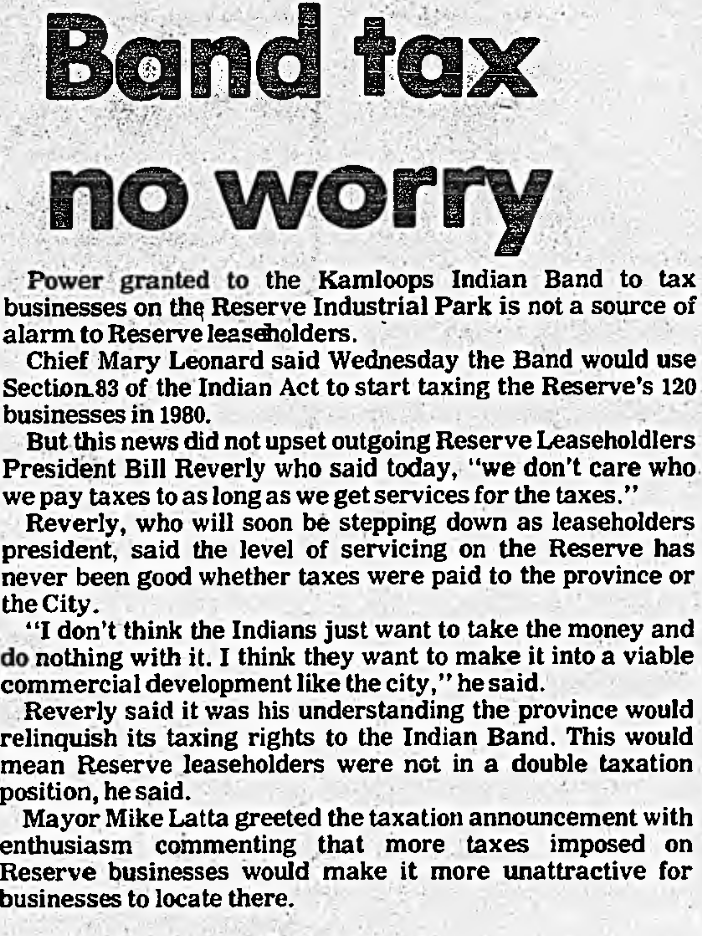

In a decision welcomed by business owners operating in the industrial park, Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc was able to begin direct taxation of businesses operating on the reserve in 1980, and therefore became able provide services like water, paved roads and fire protection to those businesses.

Kamloops Mayor Mike Latta remained openly hostile to development on the reserve, which he saw as a threat to the City of Kamloops.

In a March 1979 article published in the The Kamloops News, Kamloops Alderman Norm Fetterly publicly blasted the city council and especially Mayer Latta for their animosity towards Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc.

By the lead up to the 1980 Kamloops election, voters were demanding better behaviour from the city, especially in their dealings with Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc and the city’s own employees.

The level-headed but firm leadership of Chief Mary Leonard during these tumultuous times set the stage for the coming decades, as outlined by Mt. Paul Industrial Park general manager Randall Black in a 1982 issue of the Tk̓emlúps te Secwépemc quarterly magazine Lex’yem.

Though it has been a slow, complex and yet incomplete process, the relationship between the City of Kamloops and Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc has improved in recent decades, as expressed by both governments. So too has the appreciation for the Red Bridge.

The response to this destruction has been overwhelmingly one of solidarity, with Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc, the City of Kamloops, the New Democratic Party and the B.C. Conservatives united in their determination to rebuild.

The Wren is a community driven local news outlet. Your questions and ideas help guide what we dig into. Your feedback after we publish a story helps ensure we're always improving our reporting to better serve you

What do think about this story?