Editor’s note: As a member of Discourse Community Publishing, The Wren uses quotation marks around the word “school” because the Truth and Reconciliation Commission found residential “schools” were “an education system in name only for much of its existence.”

When Candice Day started learning her ancestral language — taking Secwepemctsín classes online during the COVID-19 pandemic — she did not imagine it would lead her to move homes and change careers.

Now, Day, a St̓uxtéws (Bonaparte) First Nation member, spends all her time working to study and revitalize Secwepemctsín.

Day started learning after connecting with two St̓uxtéws Elders from her community. After eight months, she decided to move from Vancouver to Chase to participate in the adult-language immersion program at Chief Atahm School, located in Sexqeltqín (Adams Lake Indian Band).

“I made the decision to transition out of my career in social entrepreneurship to work in language revitalization full-time,” she tells The Wren.

“It has just deepened over time my love and connection and commitment to language revitalization, learning my language, and strengthening our language.”

Now, she works mainly in what’s known as a “language nest” program for babies and toddlers, and also helps support the creation of a Secwepemctsín grammar book for immersion teachers.

Language diversity is at risk — in B.C. and globally

Secwepemctsín, the language of the Secwépemc Nation, roughly translates to “spread out people.”

Like most languages, there are various dialects within the Nation, based on community and location.

According to Day, language nests are a well-known model to those who work in language revitalization.

The language nest concept was inspired by the Māori people in Aotearoa (New Zealand) — in particular, their Māori kōhanga reo, in which Indigenous grandmothers teach their language to children as part of early-childhood immersion programs.

In language nest programs, children learn their ancestral languages starting when they are very young, as they interact with fluent or semi-fluent Indigenous language speakers.

In B.C., language diversity is at risk — and many Indigenous languages have been lost with the deaths of the last fluent speakers.

To counter this threat, language revitalization efforts are underway with the help of the First Peoples’ Cultural Council (FPCC), a 35-year-old provincial Crown Corporation that assists B.C. First Nations revitalize their culture, heritage, arts and languages.

B.C. has 34 Indigenous languages, grouped into seven language families, that represents 60 per cent of the First Nations languages in Canada, according to the FPCC.

However, globally language diversity is declining. Here in B.C. Indigenous language advocates feel they are racing against a clock to reverse the decline.

“We’re losing our speakers every year,” Day tells The Wren. “It can be an overwhelming experience to feel like we’re running out of time.”

‘Culture is wrapped up in the language’

Language is more than just a communication tool, Day says. It offers a connection to the past, and provides a bedrock for identity formation.

“Culture is wrapped up in the language — so much of our culture is our understanding of who we are as a people,” Day explains.

“There’s a cultural loss with that along with the language loss.”

The process of language sharing in First Nations communities was “forcibly interrupted by colonization and residential schools,” according to the FPCC.

That’s left Day with a strong sense of responsibility to pass on what was saved.

“Our ancestors had to hold on to this language, when essentially the attempt was to take it away from us through extreme violence through residential school,” she says. “We have a lot of respect and reverence.

“We feel a great responsibility to the language, to those that have held on to it for us and for us to carry it forward.”

Indigenous languages punished in residential ‘schools’

For more than 150 years, the residential “school” system forcibly removed an estimated 150,000 Indigenous children from their families, notes the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation.

The colonial institutions attempted cultural assimilation, often through violence; many students suffered abuse, and were forbidden to speak their languages — forced to speak either English or French. They were also prohibited from practicing traditions or customs.

Since the last institution closed in the 1990s, survivors of residential “schools” have faced intergenerational effects, among those the loss of language.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission concluded the system amounted to “cultural genocide.”

As one of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action, language revitalization is seen as vital and urgently needed on a generational level.

Day’s kyé7e (grandmother) went to the Kamloops Indian Residential School, where she lost her language, Day recounts.

“She didn’t speak it to my mom and they didn’t speak it at home,” Day says. “She understood it, and I know that talking with family members they would hear their Elders speaking it to each other, but they would never speak it to the children.”

She explains that speaking Secwepemctsín at “school” would be “punished through violence,” so her grandmother’s family “didn’t want their children to experience that.”

As a result, Day’s kí7ce (mother) did not learn the language, either. So for Day, being able to learn the language as an adult has allowed her to connect with who she is as a Secwépemc person.

“It’s also an act of resistance in learning our language,” she says, “because it was taken away from us.”

Learning Secwepemctsín

Day has been learning the language in person for three years, and in that time has found it to be both “liberating and grounding,” she says.

“It’s a way for me to honour my ancestors, and it makes me feel more connected to them,” she adds.

It’s also helped her to become much more connected to her own community and her roots.

“A lot of it is connection to community,” she says. “It’s connection to culture, because language is culture. It’s learning about our worldview as Secwépemc through the language — and that for me was really powerful.”

But it wasn’t always easy.

“Learning a language as an adult is a very challenging thing,” she says, “but also learning a heritage language or traditional language is a very vulnerable and emotional experience.”

After she moved to Chase, her experience with the language was very different from learning online. She knew immersion would be the best way to learn, however.

“It was a full-body experience,” she recalls. “It was a full-mind experience.

“It was really challenging to be immersed in the language for hours every day, and having to listen so intently to the sounds.”

Teaching Secwepemctsín

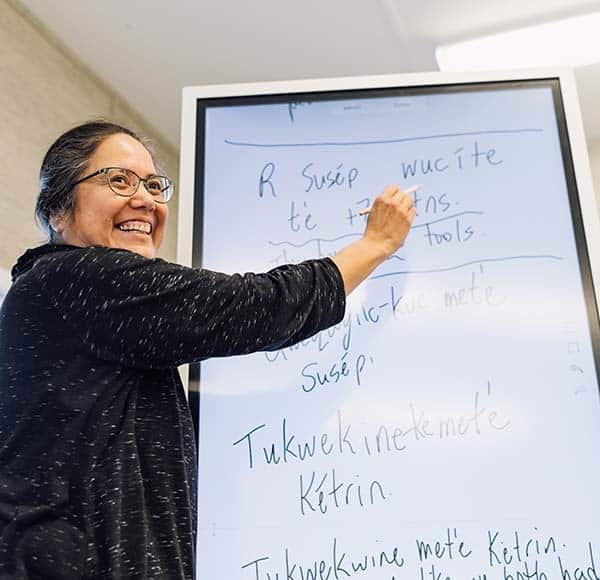

Sexqeltqín (Adams Lake Indian Band) member Janice Billy is one of the language teachers at Chief Atahm School.

Despite being the daughter of two fluent Secwepemctsín speakers, she did not grow up knowing their language.

“As they started seeing a little bit of the world away from the reserve,” Billy tells The Wren, “they thought, ‘In order for our children to be successful in society, then they better be good at English.’”

Billy has a Bachelor’s degree in education, and a Master’s in language revitalization. She has taught for 40 years — more than three-quarters of that focused on the Secwépemc immersion program.

Currently she works as a teacher for Grades 2 and 3, and teaches all her subjects in Secwepemctsín.

“I’m also a student of the language too,” Billy tells The Wren, “so a life-long learner of Secwepemctsín through my Elders, and then also through courses that are taught through the Chief Atahm School.”

Elders helped build the school when it started, and they continue to participate in its programming.

According to Billy, there are children who have been through the programming of the school and have become semi-fluent — and even some fully-fluent — speakers of the language.

Billy says Secwepemctsín is a rich and difficult language. But it needs to be taught for it to be used more widely.

“We are born on this land, and I have been born Secwépemc for a reason, and I have a language, and my people have a belief system,” she says. “They have values, they have ways to do things.

“They have customs, protocols — all of those things I think are best transmitted through the language.”

Why is language revitalization important?

There has been a gap of Indigenous language learners able to hear, understand, speak and live their lives surrounded by their language, Billy says.

“Our fluent speakers are in their 90s now,” she says. “Some of them don’t leave their houses now.

“We just need more. I don’t know if it’s more commitment on our part, or we just need more places that we can use the language.”

Elders have carried valuable knowledge through generations, including the stories of how their culture started.

“I feel that without the language, we don’t have that base,” Billy says.

As a Kyé7e (grandmother), Kí7ce (mother) and auntie herself, Billy sees language revitalization as her responsibility — to ensure that future generations will have access to it.

“Through being around the language, being taught the language, being around our Elders, that is my responsibility,” she says. “So as a responsible person, then I want to find the best way I can to get our children, to get all of us the language.”

While Billy says she believes it is possible to fully bring back Secwepemctsín to her Nation, it is a lot of hard work. She acknowledges that she, too, is still learning.

As a language learner herself still, she says she feels her entire perspective, identity, ways of being, emotions, values and beliefs “all stem from knowing Secwepemctsín,” she explains.

Kectéls-kuc (‘What they have given us’)

In late May this year, a major Indigenous languages conference brought together participants for the first time since the COVID-19 pandemic.

Before 2020, the Kectéls-kuc Conference was hosted every year or two, bringing together language advocates and teachers from Indigenous Nations across the province and country, according to Day.

“The conference is centered mostly around language teachers or language leaders working in language revitalization for their communities,” she says.

The conference also focused on several Indigenous languages, bringing together folks from all over Canada.

“Language revitalization it’s really tough, and it can be kind of lonely work,” Day says. “When you can bring everybody together, it’s really inspiring.

“It’s great for resource sharing, building connections, and just kind of keeping that fire burning. We all really need that.”

During the conference Day spoke about her work at the school, and also moderated a youth panel.

There is a full community of like-minded people, all of whom want to learn their ancestral languages and live in the ways of their people, Billy adds.

She says everyone involved in the language program wanted to invite their friends and families to attend the event — and to celebrate the progress they have made through their efforts.

“[In the conference] we wanted to share what success is, what we were, what we’re doing at the school,” Billy says. “Because everybody is at their different levels of language teaching across the province, and across Canada.”

As an immersion teacher, her role at the conference was to share how she has successfully taught children the language.

“Teaching never is static, it’s ever evolving,” Billy explains.

“It is my responsibility as a grandmother now — and it was my responsibility before as a mother and as an auntie — to make sure that the future generations and the generations to come will have the language.”

Editor’s Note July 17, 2025: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that Candice Day moved from St̓uxtéws to Sexqeltqín. In fact she moved from Vancouver to Chase, which is near Sexqeltqín.

So do we. That’s why we spend more time, more money and place more care into reporting each story. Your financial contributions, big and small, make these stories possible. Will you become a monthly supporter today?

If you've read this far, you value in-depth community news