Winter is quite a popular season amongst those who celebrate Christmas, Hanukkah, Kwanzza and more. However there are other traditions for the winter, which spans from Dec. 21 to March 20.

A popular winter holiday in North America, Christmas started originally as a Christian tradition, and before colonization many Indigenous communities around the world honoured this time of the year differently.

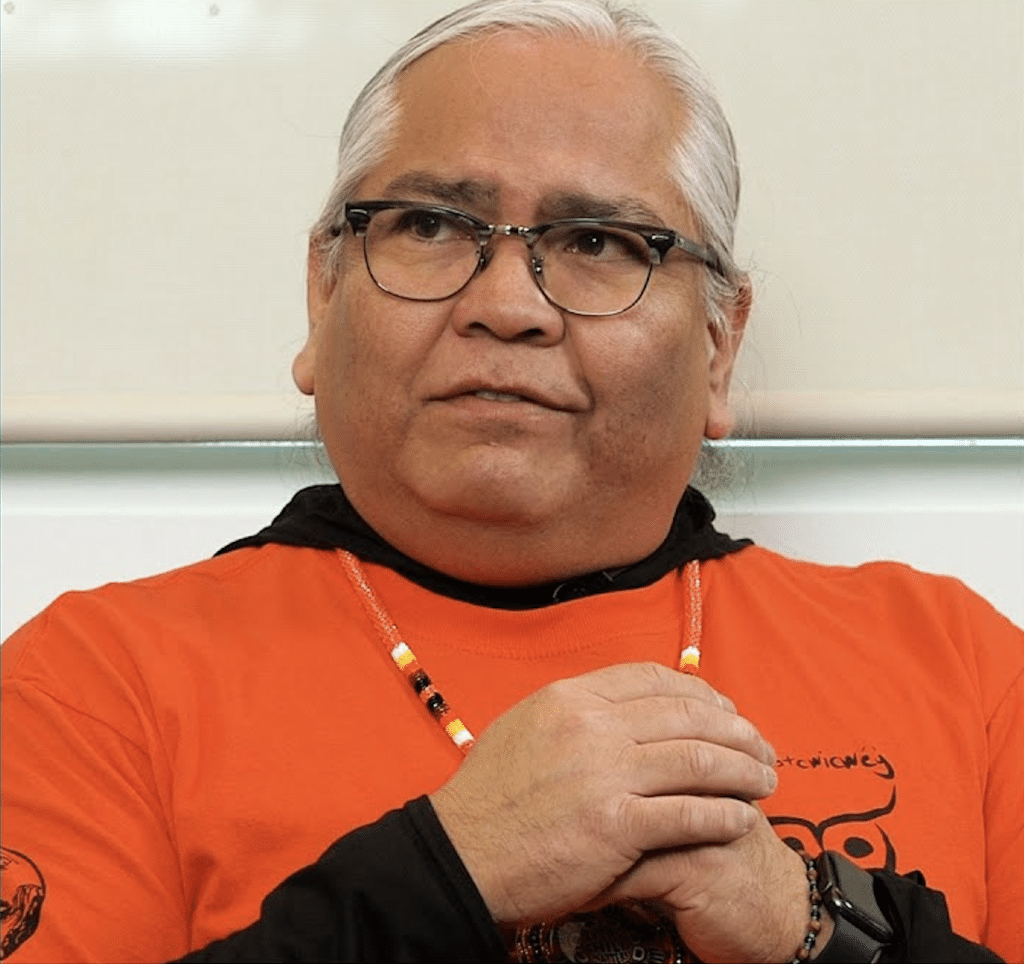

The relationship Indigenous people have with non-Indigenous winter holidays varies from person to person, Ted Gottfriedson, Secwépemc cultural advisor at the Office of Indigenous Education at Thompson Rivers University shares.

“I have come to find that the ideals of Christianity, and the cruelty that it has inflicted upon my people, I can’t reconcile those two things,” he says.

He is referring to the Catholic Church’s role specifically in the context of residential “schools,” when children from Indigenous communities were taken to institutions in order to strip them of their language and culture.

“For me, it’s not that pressure-packed season in the contemporary sense of the world,” he adds. “[We] definitely utilize the time in a way that’s important to us.”

Last year, Gottfriedson and his family spent the holiday time together without the pressures of gift-giving or any of the Christmas traditions, and not every year looks the same.

But since time immemorable, long before Christianity was brought to this continent, Indigenous peoples marked the quiet, contemplative time of year in other ways.

One example is the celebration of the winter solstice Dec. 21 when the sun is farthest away from the equator, and the day is the shortest and darkest of the year in the northern hemisphere.

During the winter solstice some First Nations hold gatherings and ceremonies while others share knowledge through storytelling and there are traditions that go uninterrupted during this time according to the First Peoples’ Cultural Foundation.

Since the days are shorter some communities take this time to rest and take care of their families and loved ones.

In the past, “there was a lot less time dedicated to gathering the resources because there actually was snow in the Kamloops area,” Gottfriedson says.

Winter brought limited mobility options, and while folks would still hunt and fish, the food consumed during this time was mostly obtained during the spring and summer months.

“When we had more downtime, that was a time that our people would share,” Gottfriedson says.

As an oral-based society, the Secwépemc people would share stsptekwll, or traditional knowledge during this time.

“Our stsptekwll contains within them [stories] our history. It contains our technology, it contains our science, it contains our morals, it contains our laws,” Gottfriedson says.

Winter offered the Secwépemc people time to dedicate to the tellings, in addition to creating new tools for upcoming seasons of harvesting and gathering.

“During the winter months, that was a big important time for us, spiritually and in terms of schooling,” Gottfriedson explains. “It was necessary to teach a kid how to be safe around the river or how to hunt. And it was definitely the time where we had our largest spiritual ceremonial gathering at winter dance.”

Winter dance

During the winter dance, the whole community would participate and other communities were invited.

It was sacred and quite protected amongst Secwépemc people, Gottfriedson explains, so what happens during the days-long event is not widely shared, but as one of the largest spiritual ceremonial gatherings, it included various components of dancing, singing, feasting and prayers. Traditionally, it was held in the largest winter home and people would have been housed there.

“It is the most sacred thing that our people did,” Gottfriedson says.

In her doctorate thesis Janice Billy states that the songs sung at the winter dance “were said to have come from the spirit world. Messages and songs were obtained from other natural forces such as plants, water or animals.”

Colonization however attempted to bring an end to the winter dance, along with other traditions.

The book Shuswap Stories reported the last Secwépemc winter dance took place around 1929.

This was due to the “criminalization of ceremonies, thus, effectively destroying Indigenous methods of teaching and transmission,” according to the text.

In the Okanagan, some syilx commemorate the winter dance, and although it is similar to the winter dances of old, there are no events quite like it in Tkʼemlúps.

“I’ve heard people say we need to bring it back. How do we do it?” Gottfriedson asks.

A lot of community members have found it challenging to bring older traditions back while also considering spiritual safety and cultural safety.

“Unfortunately, the residential school has created a lot of holes in our culture, [the Winter Dance] being one of them. There are, luckily for us, some elders who held on to that knowledge,” Gottfriedson says.

Raised with the importance of traditions and ceremonies Gottfriedson reiterates these “are not toys to be played with.”

“I’m very cautious about my spirituality, because we’re reclaiming it, and we’re doing all of those things,” Gottfriedson says.

Honouring Indigenous traditions and protecting them has been something that Gottfriedson has adopted. Although revitalizing customs like the winter dance will take time, he says he hopes to attend one eventually.

“It was the way that we prepared ourselves for the coming year,” he says. “We gave thanks for the following year, the ending of the year.”

So do we. That’s why we spend more time, more money and place more care into reporting each story. Your financial contributions, big and small, make these stories possible. Will you become a monthly supporter today?

If you've read this far, you value in-depth community news