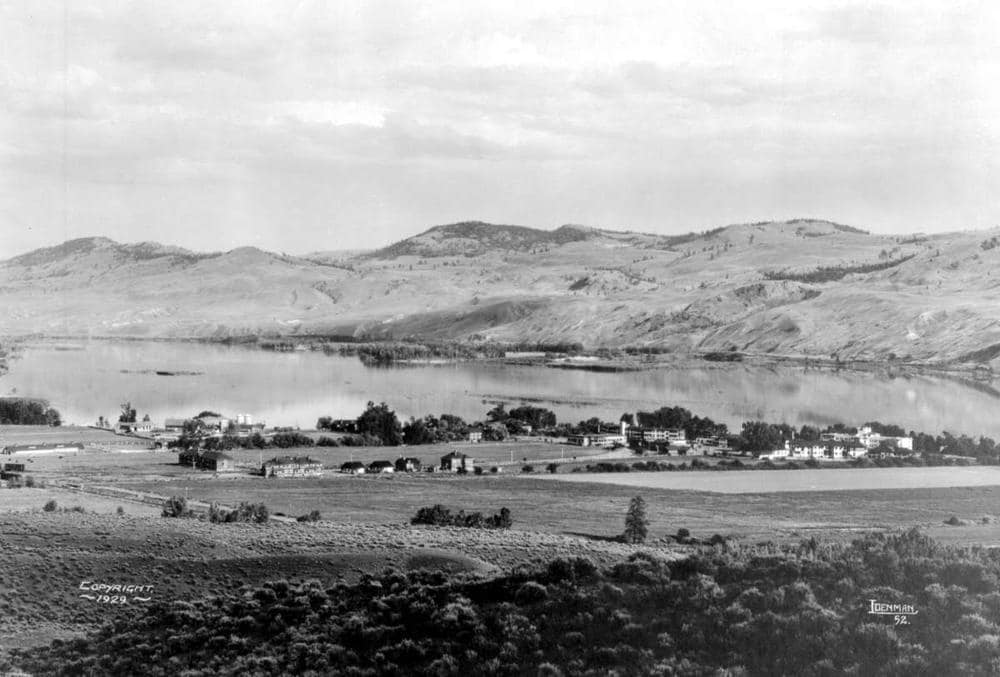

Hidden in plain sight 20 kilometres from downtown Kamloops (Tk’emlúps) are dozens of derelict buildings nestled on rich farmland — a school, a fire hall, a post office — hard to identify amidst the boarded up windows, cracking edifices and mouldy exteriors.

The community’s original purpose is captured in its former name: the Tranquille Sanatorium.

Locals are familiar with its story. Until the late 1950s, it was a quarantine zone for tuberculosis patients and an active neighbourhood for hundreds of locals, including nurses and their families.

Many Kamloopsians still have ties to the sanatorium: whether they or a friend or family member worked there or they know someone who grew up on the property. The haunting premises appear to be all that remains of its historic past, until you dig a little deeper.

This land west of Tk’emlúps — Secwépemctsín for “where the rivers meet” — is also the site of a major Secwépemc settlement dating back thousands of years.

It is called Spelemtsin, Secwépemc Elder Jeanette Jules tells The Wren, and it has been occupied by the Tk‘emlúpsemc (“the people of the confluence” now known as the Tk’emlúps te Secwe̓pemc) for time immemorial.

This rich past is evidenced by oral history and the archaeological findings buried among the sweeping structures of the old sanatorium, including ancestral burial sites among gravel pits now pitched for development.

In recent years, Spelemtsin’s millennia-long history has been eclipsed by plans for the future. The 460 acres of land were purchased by private investors in the early 1990s, and over the following few decades a series of developers have relentlessly negotiated with the province and other stakeholders to break ground on their projects.

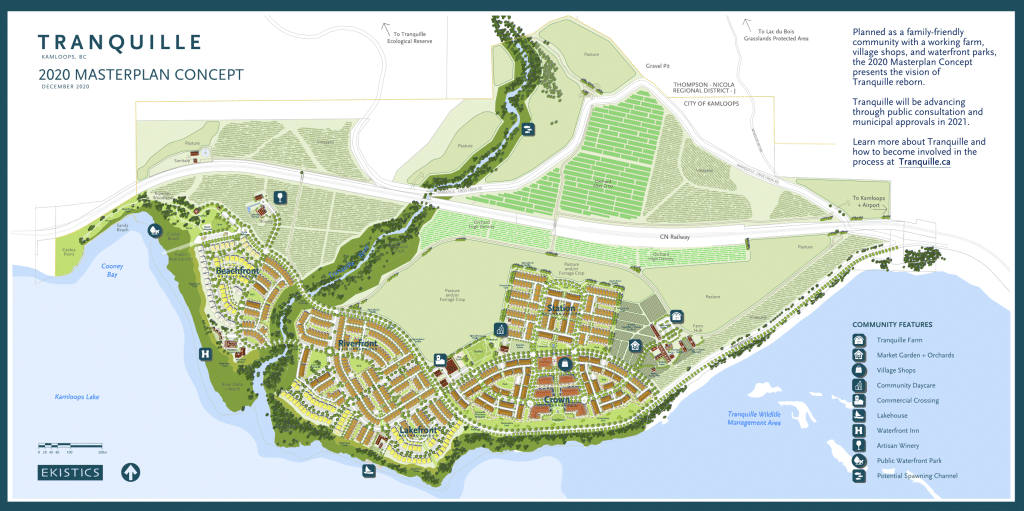

Today, Tranquille on the Lake is a multi-million-dollar development project proposed by Ignition Tranquille Developments, based in the Lower Mainland. They intend on building an “agrihood” featuring a winery, lakefront community and working farm.

The developer maintains that its latest concept plan, released in 2020, resolves the “complex, interrelated challenges” of developing this site. In a 2021 submission to the Agricultural Land Commission (ALC), the developer argues the “central problem” of the plan is “how to pay for the remediation of the site’s provincial sanitorium while ensuring public lake access and a stable future for agriculture.”

But there’s another problem, and it hasn’t received nearly the same level of scrutiny and public attention: How can this development vision be realized when sacred Secwépemc burial grounds are held within the earth, alongside millennia of cultural history?

“Every so often somebody disturbs an ancestral burial. Then we have to go and do the ceremonies that need to be done,” says Jules.

“You just need to be aware of that at some point or another, you may run into one of our ancestors that you just disturbed.”

This problem has become increasingly urgent in the context of legal recognition of First Nations’ inherent rights concerning what happens on their unceded territories.

And yet, many questions about how the developer and other levels of government are responding remain unanswered.

A rich cultural landscape

This area was also known as Pellqweqwile, translating to “has biscuitroot,” an important food once harvested here, according to Knowledge Keepers and authors Marianne and Ronald Ignace in their book Secwépemc People, Land and Laws.

For Secwépemc peoples, the mere existence of place names are evidence of title, the Ignaces explain, and the Canadian courts recognize oral histories as evidence of Indigenous use and occupation of lands.

“We’ve never signed a treaty,” says Jules, clarifying that she is speaking to The Wren on behalf of herself as a traditional Knowledge Keeper, not Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc.

“We’ve never ceded, surrendered, nor have we lost in war the title to our land. It is still our ancestral land and village.”

Thousands of years before fur traders and developers sought to make money off this land, Secwépemc peoples knew of its inherent value.

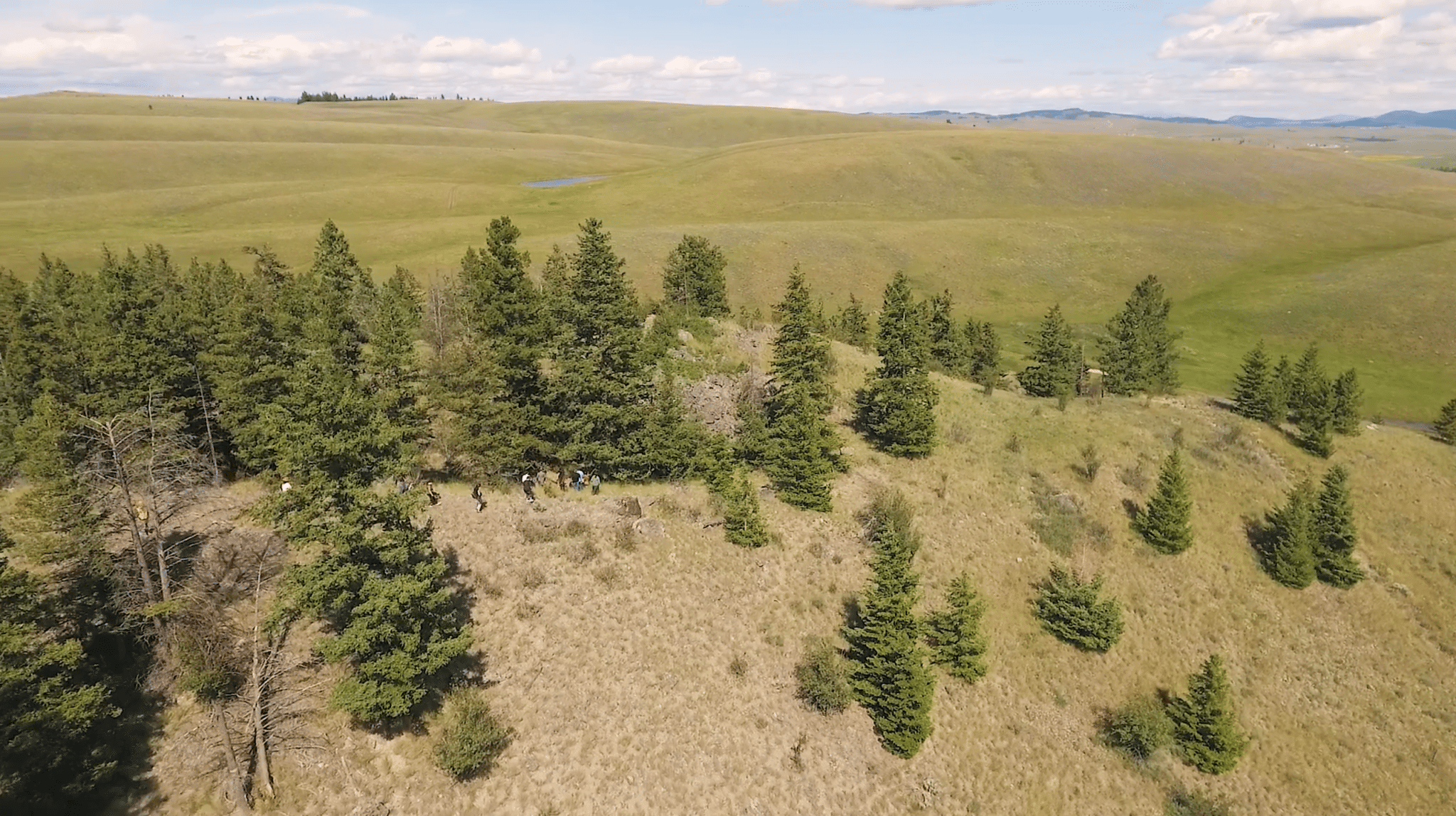

Independent archaeologist Joanne Hammond says the location’s desirability is traced back to the alluvial fan — a triangular-shaped deposit of gravel, sand and other sediment developed during the deglaciation of the Tranquille River.

This deposit rendered it ripe with a variety of medicinal foods, animals and an abundance of salmon coming up the river.

Encased among the sloping hills are archeological findings tied to Spelemtsin, including hearths and cache pits, for storing items and food.

“The richness of the environment in that alluvial fan at the mouth of the valley was pretty substantial compared to the kinds of resources that would have been available in other places nearby,” Hammond says.

“There’s no doubt that the remains that we’re seeing there represent continuous and increasingly complex occupation that developed from the serious exploitation of all those resources.”

The Secwépemc “were one with the land,” Jules says.

“We understood what the land needed,” she continues. “If the land is unhealthy, the air isn’t going to be good to breathe; if the land is unhealthy then water is not going to be healthy. That’s why we’re here today.”

European settlers also recognized Spelemtsin for its natural richness, but in a different way.

In the late 1800s, French-Canadian fur traders re-named the area after a Secwépemc Chief named Piqwemús (Pacamoos) whom they referred to as Tranquille, the French word for calm. Gold-searching fur traders farmed the fertile soil at the mouth of the Tranquille River — notably, Charles Cooney and William Fortune.

In the years that followed, Secwépemc Chiefs described a transition from friendly relations with Hudson’s Bay Company fur traders to increasing encroachment and broken promises. The colonial government was seeking newcomers to farm the land and was using its imposed laws to dispossess Secwépemc peoples of their territory.

The Cooney and Fortune families acquired parcels of Tranquille in the mid-1800s to early 1900s through a method called pre-emption, essentially permitted squatting. Settlers were given the right to stake a claim on “unreserved Crown land” — in this case, Secwépemc homelands — and purchase it for a discounted rate if they agreed to “improve” it.

Once a Crown grant was issued, the land was “alienated” and became privately owned. The only way it would be returned to the Crown is if the individual defaulted on their taxes. More than 300 acres cost Fortune, a Hudson’s Bay Company employee, $140, equivalent to roughly $3,000 today.

Despite being the caretakers of Spelemtsin, diseases brought to the region by fur traders also took hold during this time. By the turn of the 20th century, the “white plague” (tuberculosis) became the leading cause of death in the country and Fortune sold his land in 1907 to be used as a sanatorium.

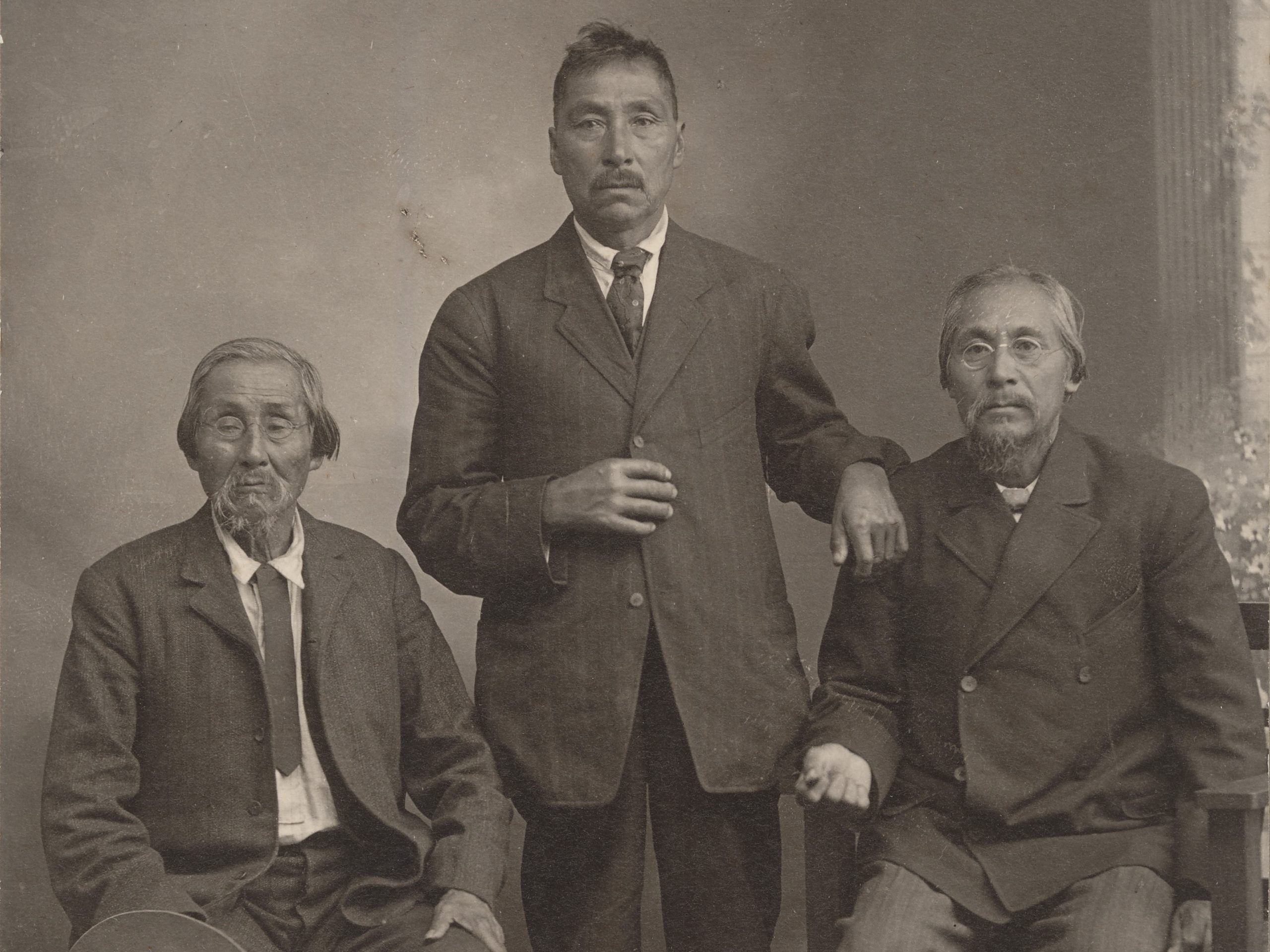

Between 1850 and 1903, a few years before the sanatorium opened, the Secwépemc population dropped from 7,200 to just over 2,100. In 1901, Kamloops was a community of just over 1,500, according to the city’s first census.

Today this is one many ancestral Secwe̓pemc villages in what’s been briefly known as Kamloops, but the Secwe̓pemc peoples haven’t gone anywhere.

“Everybody likes to say, well, here’s the extinct village (of) the Secwe̓pemc,” Jules says. “

“The people are not extinct. Our ancestors’ bones are here. Their blood runs in our veins.”

From sanatorium to ‘eco-resort’

After closing in 1958, the sanatorium was converted into a mental health facility which operated until 1984, followed by a youth detention centre. With the facilities shut down and a $70,000 tax bill owed to the City of Kamloops, the B.C. government decided to sell the land in the 1990s.

It was then that Tranquille began to catch the attention of developers. After an initial purchase and foreclosure, B.C. Wilderness Tours secured the land for $1.5 million in 2000.

They hired Tim McLeod, who still lives on the property, as Tranquille on the Lake development manager. McLeod and his wife have hosted historic tours and escape rooms at the sanatorium and previously ran the seasonal Tranquille Farm Fresh while waiting for the project to move forward. They, along with a few family members, plan to live at the new development.

In a 2009 interview with BC Business, McLeod said the team was working on a new model: “an urban-agricultural environment, that places the farm immediately next to the community.”

They had a lofty goal: build a 300-acre farm, five-star eco-resort, marina and a 1,300-unit real estate development.

But they needed investors — and more land.

Most of the property on the South Thompson River — spanning roughly the size of one hundred Pioneer Parks — is governed by the Agricultural Land Commission (ALC), the provincial entity charged with conserving the agricultural benefits of farmable land by reviewing and approving land-use proposals.

To cover the costs associated with remediating the derelict sanatorium site and make the development profitable, they have spent more than two decades trying to convert portions of protected farmland, known as Agricultural Land Reserve (ALR), to other uses like housing, a golf course and a vineyard.

Ownership of the project itself hinges on these approvals: B.C. Wilderness Tours plans to sell the property to the developer, the Ignition Group, once the farm boundaries have been finalized.

For years local groups have expressed concern about the agricultural, environmental, and social consequences of developing this area — and many still have those same concerns today.

Meanwhile, it’s been up to the developer to reconcile the existence of an ancestral village and the ancestors buried there.

Because the Tranquille property was “pre-empted” in the 1800s and sold to private interests in the 1990s, up until now, consultation with the Secwépemc Nation and its governing bodies has been limited and left to the “good faith” of the developer, Hammond explains.

The province is only required to consult on things they give authorization for. So, while applications to the ALC would be sent to the Secwépemc Nation for input, nothing requires the developer to consult with the nation on its overall plans for the property, Hammond explains.

“Nobody is required to consult with the nations or get their opinion on whether or not there should be a huge development with a vineyard and 1,500 single family homes.”

A rich archeological area

Tranquille is a particularly active area when it comes to First Nations history. Preliminary archeological work showed that the proportion of positive shovel tests, or positive results for artifacts, was extremely high compared to other areas of Kamloops, Hammond says. Shovel test pits are a standard method of early-phase archaeological investigation, used to sample an area to get a general idea of what might be found underneath.

Second to Victoria, Kamloops has the most recorded archeological sites in the province within 10 kilometres of the city.

B.C.’s Heritage Conservation Act aims to protect registered archeological sites in the province, including those identified to date at Tranquille. It also protects other sites, including burial grounds, regardless of if they are registered.

“The Heritage Conservation Act is a powerful document, because, in theory, it does protect all archaeological sites in the province,” says Simon Fraser University professor George Nicholas, who worked with Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc in the 1990s and has advocated for the protection of Indigenous heritage.

In practice though, significant gaps remain, particularly on privately owned lands.

“The reality is a little bit — or in some cases, a lot — different,” Nicholas says.

When a development is proposed, nations with a claim to particular lands are notified and given an opportunity to review proposals and identify any concerns, Nicholas explains.

“But this is very different from [First Nations] being in a position to have a more direct and more meaningful involvement in what’s happening to their traditional lands and to the heritage that is still there.”

Right now, the onus largely falls on private landowners to consult with the original title holders about the potential disturbance to archaeological sites and to mitigate that damage.

Some of the site’s legacy was identified in a 2010 Archaeological Impact Assessment (AIA), conducted under a Heritage Inspection Permit granted to the developer.

Hammond has reviewed the AIA, and from what she recalls about the maps showing the areas the Tranquille developer tested, the archaeologists shovel-tested less than one per cent of the property.

“It was basically a first dip, to get in there to get a sense of what was going on,” she says. And these samples revealed that “what is going on is huge.”

There’s “no doubt that the site includes ancestral burial grounds,” Hammond says. “All those gravel formations and terraces are stereotypical places that you would have burials in this region.”

The developer stated it hired a consultant to complete an AIA with specialists and field staff provided by Stk’emlupsemc te Secwepemc Nation (SSN) — a governance region of Secwépemc Nation representing Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc and Skeetchestn Indian Band.

They identified several archaeological sites, now registered with the B.C. Archaeology Branch, and acknowledged that more sites could be uncovered in the estimated 15 years of construction.

From what Hammond read in the AIA, Tk’emlúps and Skeetchestn had representatives on the field, but they didn’t have input on what work was done, or how.

An evolving legal landscape

SSN asserts and declares Aboriginal title and rights on its territory, including the Tranquille property.

The site “has strong ancestral ties to the Stk’emlupsemc te Secwepemc,” and the nation “has pre-existing Title and Rights to the Secwepemcúĺecw (land) where the project is proposed,” according to a 2021 submission to the ALC.

“It must be understood that SSN is the rightful owner of all resources (cultural, mineral, water, soil, forest, animal, etc.) on our Secwepemcúĺecw and as such, will be making all and any decisions regarding who, how or when these resources may be accessed.”

SSN rejects the authority colonial institutions like the ALC claim over the land.

“The Crown or a Third Party does not have the ability or right to determine who may access and develop our resources, values and laws,” according to the letter.

SSN did not respond to an interview request for this story and Tkwenem7íple7 Nikki Fraser said “Tk’emlúps has no comment at this time.”

While SSN strongly asserts and declares its title and rights to the Tranquille site, how those rights are recognized and respected by colonial institutions is less clear.

In 2015, SSN filed a lawsuit claiming title to its territory, approximately 1.25 million hectares with Kamloops and surrounding areas at its heart.

While the province and federal government decided not to green light the proposed mine that triggered the lawsuit, partly as a result of SSN’s assertion of its own impact assessment and laws, the proceedings are ongoing and a trial date has not been set.

Tranquille is considered private property, which establishes rights that are well defined in Canadian law. Private property rights are strong but not absolute, and can be limited by various laws and competing interests, such as zoning rules, permitting processes or rights to minerals held underground.

But the courts have yet to significantly contend with the existence and impact of Aboriginal title on private land, explains Darcy Lindberg, an assistant professor at the University of Victoria, who practices in the areas of Aboriginal law and human rights.

Colonial relationships with First Nations evolve, but slowly

Outside of the courts, nation-to-nation relationships are evolving in significant ways, too.

“When you think about what has occurred in the last 20 years, we’ve gone from not only the Truth and Reconciliation commission, but also UNDRIP, but also the rediscovery of the graves (in Kamloops) two years ago,” Lindberg says.

When it comes to meaningful reconciliation, the next big question is what all of these parties — whether it’s the provincial government, municipal government or private landowners — do with this information, Lindberg adds.

In 2019, British Columbia passed into law the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, which establishes the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) as the province’s framework for reconciliation.

UNDRIP calls on governments to consult with Indigenous peoples “in order to obtain their free and informed consent” before approving any project affecting their territories. B.C. has committed to bring its laws into alignment with UNDRIP and to implement an action plan to that end, while reporting regularly on progress.

Four years later, First Nations leaders have expressed frustration with the pace of change.

In a June 2022 letter to the province, cited by the ALC, SSN expressed dissatisfaction with the discussions to date with the developer and requested that higher-level engagement and negotiations occur with the province.

“What we’re seeing here is sort of the intersection of local concerns coming out of First Nations about their heritage sites being threatened,” Nicholas says. “And then on the other side of this, we have… Indigenous peoples seeking to have their rights, which they’ve never given up, recognized.”

The onus on landowners can be costly

Faced with the responsibility of identifying and mitigating potential damage to archaeological remains, developers sometimes run out of money, Hammond explains.

“It does get quite expensive when you have that much archaeology in a place,” she says.

While this should be accepted as part of the cost of developing Indigenous territory, Nicholas says, this can be a source of frustration for landowners.

“Their frustration should be directed to the province, not to First Nations peoples in general,” he says. “It should really be the province who’s picking up the costs.”

For landowners and the public, it can be a challenge just to recognize where sacred sites might exist. Known and registered archaeological records in B.C. are available on a “need to know” basis for those with an interest in a site, like First Nations, landowners, realtors or local governments, as determined by the province.

Before someone buys a property or tries to break ground on a project, it’s up to them to determine if archaeological sites exist within the boundaries before they do any work on the site.

If registered sites do exist, they must consult with an archaeologist and B.C.’s Archaeology Branch and apply for a permit to change the site.

The province approves about 500 of these permits annually — a figure that is increasing each year.

Public access to archaeological records is limited to safeguard the sites and avoid acts of vandalism or theft — what is formally known in the archaeology community as “looting.”

“I noticed over the course of an entire career in archaeology, how low those risks actually are,” Hammond says. “My perspective is that if we can’t show the public anything about what it is we’re doing, how are we going to convince them to join us in preservation efforts?…To me, it contributes to erasing Indigenous People in histories.”

Sometimes, even those who should have access to these records, don’t. This summer, an ?Esdilagh First Nation family who purchased property in Xat’sull (Soda Creek) near Williams Lake to run an agri-tourism business called on both provincial and municipal governments to flag archaeological sites to property buyers.

The province issued building permits, failing to disclose that their property sits on archaeologically significant land. The family faces possible bankruptcy, as reported by CBC News.

Ad-hoc resolutions fail to address underlying tensions

More and more, the province is stepping in to relieve these tensions — usually by buying First Nations land from private landowners.

A well-known example of this occurred at the village site and ancestral burial grounds of Shiyahwt, briefly known as Grace Islet off Salt Spring Island. The site was re-zoned for residential development in the 1970s and years later, an entrepreneur secured a site alteration permit from the heritage branch to build a luxury retirement home on top.

After a series of protests led by local First Nations, and despite opposition from the owner, the B.C. government partnered with the Nature Conservancy of Canada to purchase the land for $5.45 million in 2015.

Local nations and their allies protested for years to protect the 16 burial cairns present there, says Nicholas, who was part of a group of 50 archaeologists and 25 communities pushing for B.C. to better safeguard Indigenous ancestral burial grounds.

“How the landowner and construction crew got around the burial cairns literally was with the knowledge and permission of the archeology branch,” Nicholas says.

“I can name you probably 10 cases where the province has bought the land as a way to get around this problem. The problem remains — the problem is actually exacerbated — because First Nations values are not being respected.”

What’s next for Tranquille?

For now, the Tranquille development vision remains in a sort of limbo. But the immediate hurdle has to do with efforts to protect agricultural land, not sacred sites. The developer has yet to convince the Agricultural Land Commission (ALC) that it can develop the property in a way that sufficiently protects productive farmland.

In January 2022, the ALC denied the developer’s latest pitch, sharing skepticism that the agricultural benefit of this site would ever be realized.

“Urban redevelopment is not an appropriate means to leverage agricultural activity,” it wrote.

The developer will have to go back to the ALC with a new proposal in order to seek the exclusions it says it needs to realize the vision.

If it is successful, the developer will also need to apply for a rezoning of the property with the City of Kamloops.

Gisela Ruckert, community organizer at Transition Kamloops, believes there is room for a development that would honour the wishes of the Secwépemc while also supporting the community’s agricultural needs. But this option will remain unavailable so long as the developer continues to seek more land extensions, Transition Kamloops maintains.

Ultimately, the developer will need a site alteration permit from B.C.’s Archaeology Branch, and this step will take into account the impacts of the development on archeological sites.

The province told The Wren it will always consult with First Nations who may be affected by an application to modify a Heritage Conservation Act site.

“At this point, the developer has not made an application for a Heritage Conservation Act permit regarding the Tranquille property – something that would be required far in advance of any work on this site,” a representative from the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development wrote in an emailed statement. “Nor has the Stk’emlupsemc te Secwepemc Nation made any recent comments to the Ministry.”

When asked if the province would intervene in a dispute over the Tranquille development, the ministry said “discussion of accommodation is premature,” since no application has been made to modify the heritage site.

The developer maintains it initiated contact with chiefs and councils of Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc and Skeetchestn Indian Band in 2019 and has “continually made every possible effort to engage with the SSN,” according to a 2021 statement posted online.

On its project website, at the bottom of a page titled “respecting the land,” the developer acknowledges that “the Tranquille lands, located within the City of Kamloops, like all the land in and around Kamloops, is on the unceded territory of the Stk’emlupsemc te Secwepemc Nation.”

The developer also acknowledges that ongoing attention to the site’s archeological legacy will be required.

“Archaeology work at Tranquille has been and will continue to be managed by professional archaeologists who are guided by current provincial legislation and respect for appropriate First Nations protocols,” property manager Tim McLeod told The Wren.

The path ahead

First Nations have protected their heritage sites since time immemorial and have long argued that the Heritage Conservation Act needs better reflect their rights, laws and values, pointing out its hypocrisies: Burial sites from 1846 onwards are protected under B.C.’s Cremation, Interment and Funeral Services Act.

But burial sites that predate the arrival of European settlers hold fewer protections.

To resolve inequities like these, the Heritage Conservation Act Transformation Project, currently underway, aims to bring the legislation into alignment with UNDRIP and to better protect the rights of Indigenous peoples.

“Whatever the Secwépemc want to do with their heritage is their business,” as Nicholas puts it.

Around the world, colonial governments are starting to “read the fine print” of having signed on to UNDRIP, Nicholas says.

“In order to make the provisions of UNDRIP work, means that the government and various agencies within have to give up at least some degree of control. … And this is going to be a huge bottleneck, because governments are loath to do this.”

In 2022, the province began formally engaging with First Nations, including Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc, to understand what reforms to the heritage act are most urgently needed. Among the priorities identified in a summary report: First Nations should have the authority and funding to choose which sites to protect and these protections must be enforced.

Meanwhile, landowners can also take part in acts of reconciliation, says Darcy Lindberg, assistant professor at the University of Victoria.

“We’ve seen it in British Columbia, and then Alberta as well, where private landowners — as their own sort of individual acts of reconciliation — have returned lands to Indigenous nations as well,” he says.

This happened in northern Secwépemc territory late last year. As part of the province’s treaty negotiations with the Stswecem’c Xget’tem First Nation, a rancher in Williams Lake sold his 7,800 hectare property and grazing rights to the B.C. government for the $16 million he purchased it for so the land could be returned to the nation. To further his contributions towards reconciliation, the rancher decided to invest the proceeds in an environmental stewardship trust.

“The biggest misconception is that everything is going to be flipped on its head when these sort of title decisions are made or acts of reconciliation occur,” Lindberg says. “But really, what it means is Indigenous peoples have more of an equal stake in how people are living together.”

Lindberg, whose family comes from maskwâcîs (Samson Cree Nation) in Alberta and the Battleford-area in Saskatchewan, says there are a number of sensitives to be considered with situations like Tranquille, whether it’s available resources, internal negotiations or the fact that there has been a long interruption of governance over certain areas of Indigenous life.

For Hammond, the most important step is acknowledging these are stolen lands and figuring out how to make reparations on them.

“And that’s everybody’s business: the developers, and the city and the province.”

Secwépemc Elder Jeanette Jules points to the 1910 Memorial to Sir Wilfrid Laurier, a letter to the premier from Secwépemc, Syilx and Nlaka’pamux chiefs. The letter welcomed settlers and requested an equal chance at making a living.

“The ordinary citizen of British Columbia — that’s not the fight,” Jules says. “But that’s what people make it out to be.”

Jules wants everyone to understand that the past isn’t buried: it’s still very much present. To move forward, we all have a duty to respect and take care of the land we live on, and to honour those who have been laid to rest underneath.

“One of the biggest things everybody needs to understand when we talk about time immemorial, and we talk about the people of Secwépemc; people move here, and then people move away. We stay here, we don’t leave. We’re still here. And we will continue to be here.”

So do we. That’s why we spend more time, more money and place more care into reporting each story. Your financial contributions, big and small, make these stories possible. Will you become a monthly supporter today?

If you've read this far, you value in-depth community news