Editor’s note: As a member of Discourse Community Publishing, The Wren uses quotation marks around the word “school” because the Truth and Reconciliation Commission found residential “schools” were “an education system in name only for much of its existence.” The Indian Residential School Survivors Society crisis line is available any time at 1-800-721-0066. Please reach out if you need support.

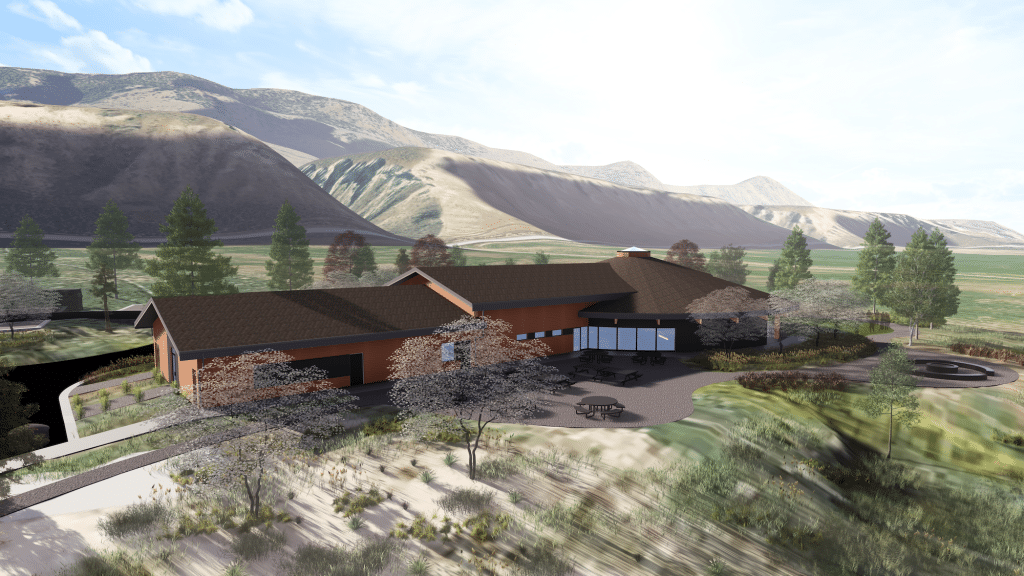

A new healing centre now under construction at Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Nation aims to offer residential “school” survivors and their descendants a place of safety and care.

In September, the First Nation held a job fair for its members to find construction work on the long-anticipated Healing House, which broke ground in late July after several years of planning.

In an interview, Kúkwpi7 (Chief) Rosanne Casimir says she envisions the facility as somewhere Secwépemc people can reclaim and pass their knowledge to future generations — before the current generation of Elders passes away, taking that wisdom with them.

“Knowing that we’re going to be connected with the land, working with the land and to be able to revitalize that connection in a good meaningful way symbolizes the whole Healing House project,” she tells The Wren.

“It’s about reclamation, resilience and self-determination.”

Finally starting construction was a historic milestone in the community’s quest for justice for colonial harms — five years after Casimir revealed archeological scans had found evidence suggesting 215 unmarked children’s graves near Kamloops Indian Residential School (KIRS).

But the shocking announcement also surfaced enormous pain across the First Nation.

In its wake, the idea emerged to build Healing House: a way to help members move forward, while bringing in Secwépemc values, language and cultural revitalization.

As the Truth and Reconciliation Commission declared in 2015, residential “schools” were an act of cultural genocide.

They aimed to “destroy the political and social institutions” of Indigenous Peoples, the commission noted, and “to prevent the transmission of cultural values and identity from one generation to the next.”

Once complete, the Healing House project will also serve as a place of refuge and healing for Kamloops Indian Residential School (KIRS) survivors and their descendants, as the nation continues investigating the fates and names of the children who never returned home to their families.

A $12.5-million project for survivors and future generations

The idea for a Healing House arose after Casimir’s announcement of the 215 ground-penetrating radar anomalies in mid-2021, and the international media storm that followed.

These anomalies are strongly suspected to be unmarked graves of children who attended the KIRS. That conclusion, Casimir says, is based on testimonies of KIRS survivors, preliminary findings of a juvenile rib bone and tooth, and the expertise of Sarah Beaulieu, who specializes in using ground-penetrating radar to find unmarked graves.

“It was so scary and horrific to think about how our Elders and survivors who attended the residential school would be impacted from that announcement,” Casimir reflects, five years after the public announcement.

As the nation worked quietly behind the scenes to figure out how to deliver its shocking findings to community members, a leak to the media forced them to make a public announcement about the 215 suspected graves.

Because of the leak, the findings would be revealed to the world — leaving a very small window to inform all Tk’emlúps members and offer support.

“It was very important to share from our perspective what had taken place, in a good, meaningful and respectful way,” she recalls. “But in the same token, it doesn’t matter how good our intentions were. It still wasn’t good enough.”

“It was difficult knowing the impact it would have, knowing the past pains and traumas of the residential school.”

From there everything happened all at once, she recounts.

She had many discussions with former and current leaders, members, and an influx of outsiders wanting to visit.

The response was overwhelming, far beyond what Tk’emlúps expected.

“People were grieving,” Casimir says, “and many had suffered life-long effects.”

A survivor’s generosity sparked a big idea

Even though survivors saw Canada make some steps forward — for instance the 2006 settlement agreement, followed by former Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s 2008 apology — there were “still a lot of steps that were missing,” Casimir recalls.

For her community, the challenge then became what its leaders could do to support their people and everyone affected by revelations about the archeologists’ findings near KIRS.

A big source of inspiration came from the gift survivor Kenneth Jensen provided to Tk’emlúps with his residential school settlement money, Casimir recounts.

As a part of his personal healing journey, he designed and financed a memorial that now stands in front of the former KIRS dedicated to the survivors of the institution.

“It was a reminder of the importance of healing,” she says, “and for him it was about taking back his childhood spirit.”

She says that his gift emphasized to her just how important healing is, and what inspired Tk’emlúps to pursue a healing centre.

In the wake of the ground-penetrating radar results, then-Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced he would visit the site.

His staff asked about concrete ways Ottawa could support the First Nation’s investigation into missing children — and how to support survivors as they grapple with trauma.

“The only thing that stood out for me is healing,” she says. “A healing house that is separate from the residential school — a place for someone to feel at home and safe in a non-colonial kind of system that is more grounded within our cultural, traditional values.”

Before Trudeau arrived, she let him know how important this was. She wanted to secure a federal commitment to address the “school’s” historical impacts — but more importantly, to also build a legacy of hope for her community members.

Her request bore fruit; Ottawa pledged $12.5 million for the First Nation’s Healing House proposal.

Healing in a Secwépemc way

The planning of the key elements of the Healing House has been an all-hands-on-deck effort, including engagement sessions with a wide range of band members.

Through those sessions, the project’s planners identified what healing might look like for the community, and what such a space should look like, how it would bring people together, and how it would incorporate traditional culture and healing practices.

Casimir notes that not all survivors of KIRS are from the Secwépemc Nation, so it’s important for the Healing House to also recognize and honour children sent to the “school” from other nations, with different cultural practices.

She wanted to respectfully include those nations’ beliefs too.

One key priority for the proposed location was that it be far from the residential “school,” on land seen as more culturally safe for those traumatized by the institution.

That way, guests could feel comfortable visiting, grounded in the land and with the Creator above.

Another priority was for the new facility to be near water, and the sacred and healing qualities it offers in many Indigenous people’s worldviews, including Secwépemc.

Once complete, its planners say they’ll bring in knowledge keepers to offer workshops, such as how to make pine needle baskets, traditional tools, and drums.

There will be a medicine kitchen to teach how to prepare and preserve traditional medicines, and how to use them.

Healing House will also feature smaller rooms for counselling and personal prayer, offering culturally safe places — offering sage, sweet grass, medicines, drums and traditional decor.

There will also be larger community gathering spaces for group healing activities and ceremonies.

She says that traditionally, Secwépemc people cleansed themselves in sweat lodges, so those will be an important component of Healing House, too.

Both a modern sauna and traditional sweat lodges will be available, with the latter located near the river.

“It’s about being able to bring in those cultural traditional values, to be able to sweat and pray and to be one with the Creator,” she says.

Because so many people carry trauma, they want to provide the resources and nurturing space to support their healing journeys.

“We can’t force others to heal,” she explains, “but we want to provide that opportunity and those resources to be able to support them.”

Another key aspect will be the revitalization of the Secwépemctsin language.

A primary goal of the residential “school” system was to break the chain of language transmission and force the exclusive use of English or French on Indigenous children.

Casimir says many community members, including herself, are from a generation that still has far to go to fully learn their language. But it is something they feel they must pass on to the next generation.

Languages are more than just words, she emphasizes; they are a system of knowledge that reflect how cultures conceptualize the world and their values and roles in it.

When a language becomes extinct, it erases a people’s unique philosophy, history and way of knowing.

Overcoming obstacles in the centre’s path

While Casimir says there’s been much support from the local community and beyond, she’s also encountered some barriers along the way.

One of those, she says, was learning the Government of Canada’s $12.5 million funding would not come to Tk’emlúps directly, but would be disbursed through a third party, the First Nations Health Authority (FNHA).

“So there was some miscommunication in that aspect,” she recounts. “In all my discussions with the federal government, it was always about helping to support our community — and not creating another layer of complexity.”

Although she believes the government had good intentions to support her community’s needs, the First Nation was disappointed Ottawa insisted on funding the Healing House through another agency, not directly as they had expected.

Staff in the band’s department responsible for Le Estcwicwéy̓ (the missing children) from KIRS have been working with FNHA, hoping to get that money into the community as intended, Casimir says, “and have the federal government understand the rationale for that.”

Another challenge was finding a site for the centre.

Originally a part of the Kamloops Indian Reserve 1, the sliver of land where Healing House is being built was illegally taken from the band during the Second World War.

In 1999, Tk’emlúps re-acquired the land when it bought Harper Ranch — now known as Spiyu7ullucw Ranch. The property remains fee-simple land within the province’s Agricultural Land Reserve (ALR).

Because of strict protections regulating how ALR land may be used, it took more than two years to get approval to build Healing House there.

The paperwork to reintegrate that land into the reserve has been signed. But it remains a long bureaucratic process involving three levels of government: provincial, federal, and the Thompson-Nicola Regional District, which has supported the First Nation’s efforts.

‘Power to create the most incredible future’

Because each generation has been impacted differently by the residential “school,” healing will require multiple approaches and supports.

The bigger vision for the Healing House is that it be centred within Secwépemc cultural values.

To its visionaries, they hope it can help revitalize the community. By closely involving Elders, knowledge keepers and families, they hope to support their healing, but also to bridge gaps between generations and within families.

“I want to be a part of a community that’s taking pride in who they are as individuals,” Casimir explains, “to know that they are resilient and thriving in a place and a time where the traumas of the past no longer impact them.

“Today we have the power to create the most incredible future.”

As Casimir sees it, the facility isn’t going to be just about healing from the past, however. It’s also about building a long-term foundation for healthy families.

She says the Band Council has been doing everything it can to support survivors and Elders; now they want to look after their youth and future generations, too.

“What we do has to benefit them,” she reflects. “That is the foundational piece for creating those positive futures for our children and for those not yet born.”

She dreams that the sacred space offered through the Healing House project will empower her people to reconnect with each other and their culture.

“We are reclaiming our future,” she tells The Wren, hopefully, “reclaiming who we are as a community, taking back and revitalizing our language and culture, to lift up our children so that they can learn those values.

“It’s going to be an incredible place that’s going to incorporate all of that.”

So do we. That’s why we spend more time, more money and place more care into reporting each story. Your financial contributions, big and small, make these stories possible. Will you become a monthly supporter today?

If you've read this far, you value in-depth community news