Kamloops, an Anglicised version of the Secwepemctsin name T’kemlups, typically upholds a founding story of trappers and trading posts; a city built by European settlers.

M.S. Wade’s 1912 The Founding of Kamloops: A Story of 100 Years Ago is a short publication filled with black and white photos of historic homes – a “modern” depiction of a city nestled in British Columbia’s Interior that came to be thanks to white men.

“From a mere trading post it became a village,” Wade concludes. “Then came the Canadian Pacific railway in 1885 and Kamloops became a town; next followed incorporation as a city and the dawn of a new era.”

There’s good, grassroots news in town! Your weekly dose of all things Kamloops (Tk’emlúps). Unsubscribe anytime.

Get The Wren’s latest stories

straight to your inbox

But the real story is preserved at the mouth of places like the Tranquille River; etched into the gravel promontories and sloped landforms where archaeological evidence and ancient accounts tell a much bigger tale about the history of the land we live on.

~12,000 years ago

Secwépemc peoples have ties to their homelands since time immemorial. Humans are said to have first occupied the Arrow Lakes and areas of the upper Columbia River Valley around the end of the last Ice Age.

~9,750 years ago

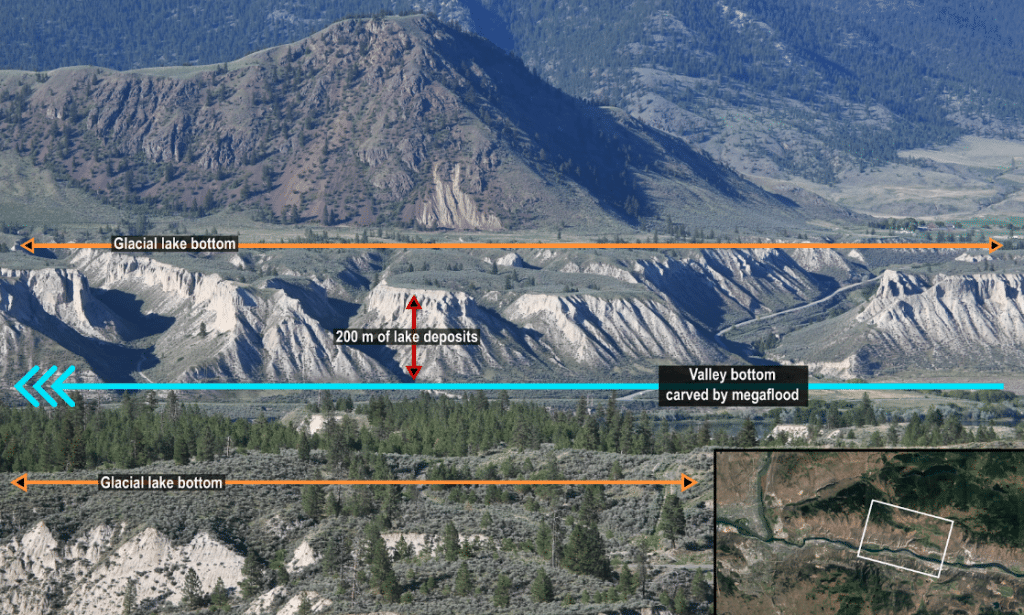

Glacial Lake Thompson drains with the breaking of an ice dam near Spences Bridge. Establishment of the Thompson Rivers

~7,500 years ago

Oldest dated archaeological remains at Tranquille.

~5,000 years ago

Several thriving Secwépemc communities formed Tk’emlúps, a village site made up of pithomes — oval, circular or rectangular structures made of timber and built into the ground— to house families during the winter. Secwépemc peoples were living in complex socially stratified and technologically innovative societies. With more than 150 pithomes, it is likely to have been one of the largest villages in the plateau region between the coastal and Rocky Mountains.

1700s

Thirty two distinct communities with an estimated population of 12,000 were spread out across the expansive Secwépemc’ulecw territory, stretching to the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains and west to the Fraser River. Archeologists have uncovered a number of historic village sites up and down the banks of the North and South Thompson Rivers ranging in size from 10 to over 100 pit homes. Tk’emlúps settlements included Tranquille Flats, Monte Creek, Rivershore, Tranquille Creek, Tranquille River, McClure Flats and Cherry Creek.

1800s

1811: Settler trader David Stuart of the New York-based Pacific Fur Company and his comrades “made their way to the large Indian Village in the junction of the North and South Thompson Rivers,” writes Mark Wade, where they spent the winter learning skills. With this knowledge they begin trading with Secwépemc communities.

The Fort Kamloops log cabin, possibly one of the oldest colonial buildings in B.C., still stands today – rescued and restored as a historical monument at the Kamloops Museum.

1821: A merger between the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) and North West Company brought all British fur trading operations, including Fort Kamloops, under the HBC banner.

1841 (Approx): Chief Piqwemús died mysteriously. His nickname Tranquille, given by francophone fur traders for his tranquil nature, gave the area its modern name.

1850: Diseases brought by Europeans begin to take hold on Secwe̓pemc peoples.

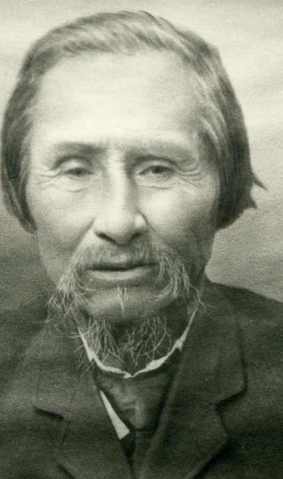

1855 (Approx): Chief Louis Clexlixqen was appointed Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Chief.

1857: Gold was discovered along some tributaries to the Thompson River. Thousands of American gold-seeking miners begin to settle in the territory. Secwépemc peoples resist by ousting miners to protect resources like salmon and their sovereignty.

1858 (Approx): The main lodgings in Kamloops were fur trader cabins, with some being built over old pit house depressions repurposed as root cellars.

1862: A smallpox epidemic further harmed Secwe̓pemc lineages.

Around this time, the governor of the new colony of British Columbia, James Douglas, offered settlers pre-emption: the right to acquire unceded Secwépemc land in exchange for commitments to “improve” it through agriculture.

1862: William Fortune from Yorkshire arrived on the shores of Kamloops after paddling his way down the North Thompson River with the Overlanders.

1864: Joseph Trutch became the new governor and used the colony’s imposed laws to further dispossess Secwépemc peoples of their territory.

1869: William Fortune acquired roughly half Tranquille property through pre-emption. The 320 acres cost the Hudson’s Bay Company employee $140, equivalent to $3,055.26 today.

Charles Cooney from Washington State acquired the other half of the property that same year and married a Carrier woman (Dene people), Elizabeth Allard.

1876: The Indian Act was imposed, dividing the Secwépemc into 17 bands and forcibly confining people to tiny fractions of their homelands.

1893: Kamloops was incorporated as a city.

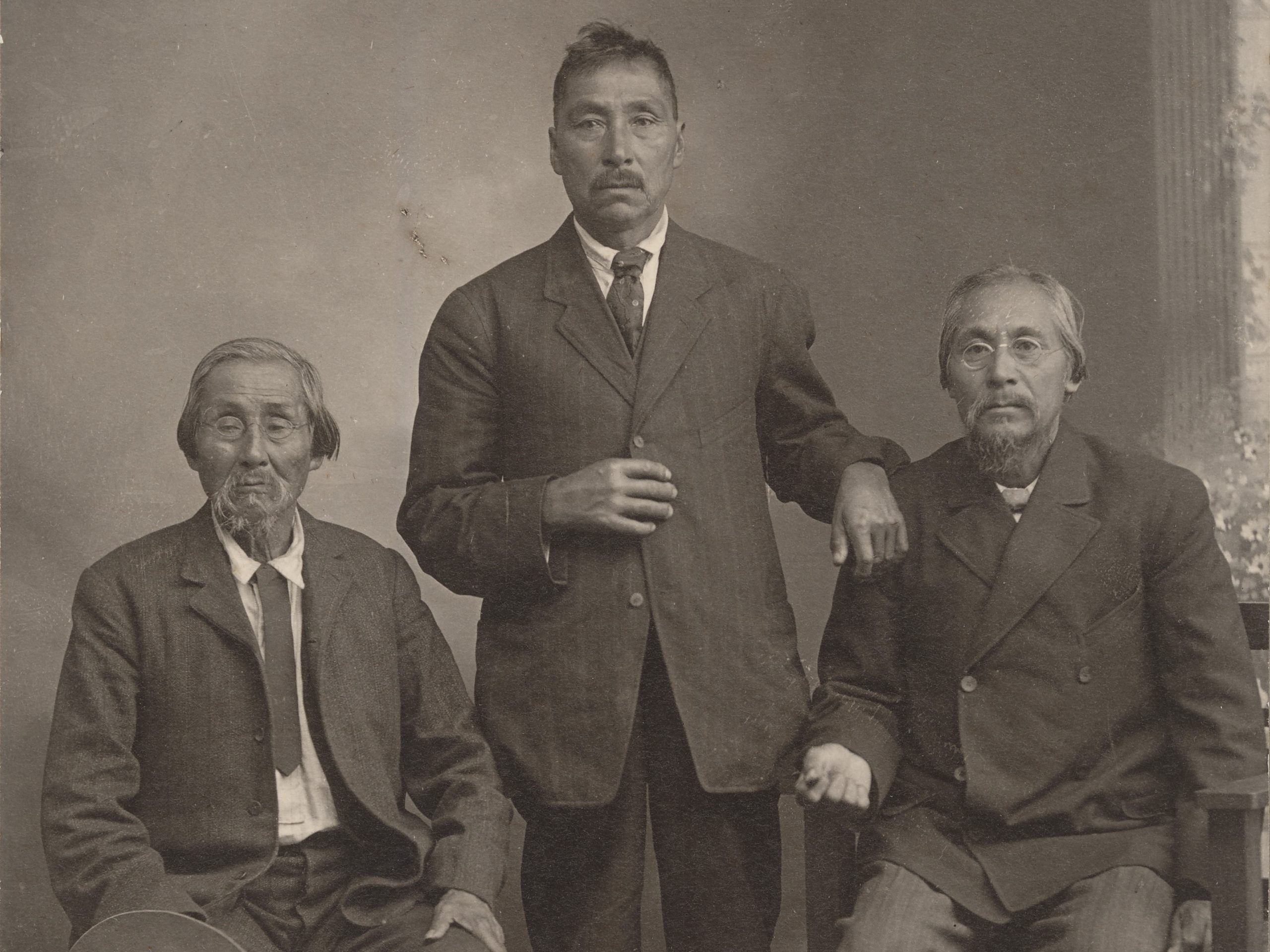

1897: During the anthropological Jesup North Pacific Expedition, 25-year-old Harlan Smith travelled to Tk’emlúps under the direction of Trutch, where he met Chief Louis and began excavating at Tk’emlups village sites.

Against the wishes of the Secwépemc, he began to unearth human remains and sent artefacts to the American Museum of Natural History. These items have not yet been repatriated to the Secwépemc Nation.

Under Chief Louis’ leadership, the boundaries of the Tk’emlups reserve were extended to “seven miles by seven miles, including five different hunting and fishing sites,” according to Traditional Knowledge Keeper, Diena Jules, likely the only time this occurred.

1900s

1901: The City of Kamloops recorded a population of just over 1,500 in its first census.

1906: The Federal Department of Indian Affairs census recorded the Secwe̓pemc population size as 2,236.

1907: By the turn of the 20th century, the “white plague” (tuberculosis) was the leading cause of death in the country. Fortune sold his land to be used as a sanatorium: the first tuberculosis facility west of Ontario.

Crowding and urbanization were contributing factors to contracting tuberculosis, and one reason sanatoriums were built in rural settings was so patients could get fresh air, according to Ken Favrholdt, a local historian and former curator-archivist of the Kamloops Museum and Archives.

“The wind blows up the lake from the west so Tranquille would be a good location, (and) any pollution from Kamloops’ mills in the early days would not reach Tranquille,” Favrholdt explains.

1910s

1910: The Secwe̓pemc Chiefs presented a document known as the Memorial to then Prime Minister Sir Wilfred Laurier to share their grievances and assert the persistence of their title and sovereignty. The letter states that they never accepted reservations as settlement, nor did they sign any papers or make any treaties.

“They [settlers] found us happy, healthy, strong and numerous ” the letter states. As settlement accelerated, “They told us to have no fear, the queens laws would prevail in this country, and everything would be well for the Indians here.”

Through these reserves, the Secwépemc occupied less than one percent of their approximately 145,000 square kilometre traditional territory. Secwe̓pemc Peoples have continued to resist the occupation of their lands ever since.

1917: Charles Cooney died. Prior to his passing, he requested the ranch stay with his family. The B.C. government pressured his wife, Elizabeth, to sell it.

1920s

1921: The government absorbed the British Columbia Anti-Tuberculosis Society and the land was acquired by the province.

1922: The provincial government purchased the neighbouring 580-acre Cooney property for $47,356 and expanded the sanatorium. In the 1920s, the province also dammed the Tranquille River for agriculture.

1930s – 1940s

Tranquille Sanatorium grew into an expansive agricultural community of over 600 tuberculosis patients and staff, complete with community gardens and essential services to accommodate its residents.

“Nurses lived on site, and there were quite a large number of patients and staff. They had a farm,” says historian Ken Favrholdt. “There was always a road into Kamloops after 1910 so people could purchase what they needed in town, but they grew a lot of their own foods. It was a real town in itself.”

1950s

1958: The sanatorium closed and was converted into a mental health facility. At its peak, the facility was home to about 700 residents, roughly a quarter of the provincial institutionalized population of people with developmental and intellectual disabilities.

At this time the site consisted of more than 40 buildings including four designated hospitals.

1960s

A human skeleton dated at 8,400 years old, the oldest known human remains in the Interior, was found about 30 kilometres east of Kamloops. Today he is referred to as The Gore Creek Man.

1970s

The Tranquille Sanatorium and surrounding area amalgamated with the City of Kamloops, but the city had no interest in taking over the site due to maintenance costs.

1980s

The focus of archaeology shifted from academic research to archaeological impact assessments (AIA’s) and land development permits, as the courts clarify the Crown’s obligation to First Nations regarding their Aboriginal title.

1984: The province closed the health facility after political and social attitudes toward institutionalized mental health care began to shift. The facility was the third-largest employer for local residents and the decision was protested. The site was briefly converted into a youth detention centre.

1989: The province submitted an application to the Agricultural Land Commission (ALC) to exclude the crumbling 32-hectare Tranquille Santorium site so they could sell to a developer. The ALC approved the application and included conditions such as buffering and fencing.

1990s

1991: Giovanni Camporese, president of A&A Foods, purchased the Tranquille property and named it after his birthplace in Italy: Padova City. The successful businessman’s plans for a golf course and marina never got off the ground.

1997: Camporese foreclosed after defaulting on his mortgage, held by the province. The province repossessed the property and placed it back on the market.

2000s

2000: B.C. Wilderness Tours secured the land for $1.5 million through a court-ordered sale. They hired Tim McLeod, who moved onto the property as the development manager.

2006: B.C. Wilderness Tours works toward its vision of an eco-agri resort and golf course. They submitted an application to the Agricultural Land Commission (ALC) to exclude 47.6 hectares from the Agricultural Land Reserve (ALR) to build 320 single family homes, 950 multi-family homes as well as commercial components. The proposal is refused by the commission on the grounds that the land has good agricultural capability, but the developer is encouraged to submit a revised application.

2007: B.C. Wilderness Tours re-submitted an application to reduce the ALR exclusion area from 47.56 to about 38 hectares for residential/resort development and non-farm use for a golf course. The Commission agreed with the instruction to move forward in phases.

2008: The Tranquille on the Lake Neighbourhood Plan was approved by Kamloops City Council and adopted into the Kamloops Official Community Plan (KAMPLAN).

2010s

2010: B.C. Wilderness Tours hired Madrone Environmental Services to undertake an Archaeological Impact Assessment (AIA). Seven archaeological sites are registered.

2011: B.C. Wilderness Tours submitted a new application to the ALC to request exclusions, most of which are denied save for the equestrian park, RV park and farm market. The ALC acknowledges seven archaeological sites based on the AIA produced by Madrone.

2012: The developer submitted another request to the ALC to reconsider components previously denied. In response, the commission requested a more complete development plan.

2015: Stk’emlupsemc te Secwepemc Nation filed a lawsuit declaring title to their territory, approximately 1.25 million hectares, with Kamloops and surrounding areas at its heart.

2016: B.C. Wilderness Tours listed Tranquille on the Lake for $15.9 million in a bid to attract international investors as there is little interest locally.

2020s

2020: B.C. Wilderness Tours teams up with developer Ignition Group and releases the Tranquille on the Lake concept plan.

2022: The City of Kamloops, on behalf of B.C. Wilderness Tours, submitted a new application to the ALC requesting 52 hectares of exclusions to support the development, which the developer said involves significant cost related to decommissioning the old sanatorium site. The ALC refused on grounds that the requests are “not consistent” with the ALR’s aim to protect farmland.

In their review, the ALC acknowledged the Stk’emlúpsemc te Secwepemc Nation’s claims of Aboriginal title and rights in the area. But they state: “Insofar as the SSN’s position might be interpreted as challenging the Panel’s jurisdiction to make a decision on this Application, the Panel finds it has statutory jurisdiction …to decide this Application.”

2022: Peller Estates signed a memorandum of understanding with Ignition Tranquille Developments to explore the viability of a vineyard at Tranquille on the Lake.

The Ignition Group has a contract to purchase the land from B.C. Wilderness Tours once a long list of challenges — from remediation of the sanatorium to land acquisition — have been addressed.

Editor’s note Jan. 29, 2024: An earlier version of this article misstated Chief Piqwemús (Tranquille) was head of Pellqweqwile, near the mouth of the Tranquille River.

So do we. That’s why we spend more time, more money and place more care into reporting each story. Your financial contributions, big and small, make these stories possible. Will you become a monthly supporter today?

If you've read this far, you value in-depth community news